EAST MEETS WEST:

How Cultural Attitudes and Belief Systems Influence Zoo Design

A paper presented at the Zoo Design Conference, 5 - 7 April 2017, in Wroclaw, Poland

Zoos can be seen as a cultural expression of society. In this talk I will address the process of planning and implementing zoos with a focus on regional differences, particularly in Asia where I have mostly worked.

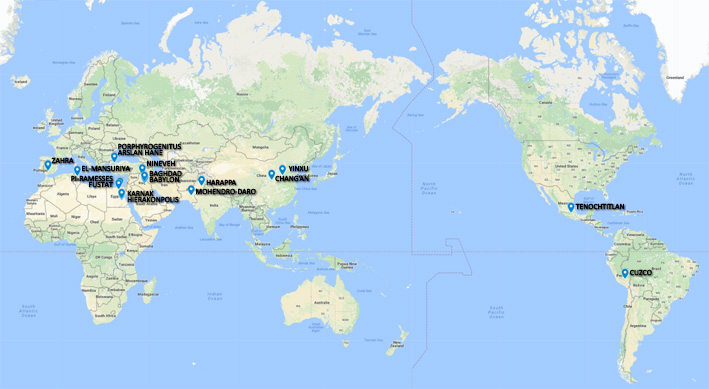

Zoos in the modern sense arose in Europe in the 19thC. But more generally, there have been zoos for as long as humans have lived in cities.

Although none of these ancient zoos survived beyond mediaeval times, I believe animal keeping traditions and practices continued and persist in these regions until today. This fact informs present day attitudes to animals.

The modern idea of zoos spread rapidly not only in North America but in many parts of what would come to be known in the 20thC as the Third World and more recently, the Global South.

Many zoos were founded under colonial rule for the benefit of the colonists. In the postcolonial world, it became a mark of civic pride and social progress to maintain these zoos or build new ones where they did not exist.

By and large, these zoos would follow the style then prevalent in the West. So the more recently established zoos leapfrogged several stages of development and innovation that took place since London Zoo first set the mould of a scientific institution for public education and entertainment.

Pride is not the only motive driving zoo development:

- Zoos are genuinely seen as a social good;

- They provide a recreation outlet;

- Individuals may drive zoo projects simply because they like animals;

- Developers may proffer a zoo to ease approval for a larger real estate development or as a 'loss leader' to increase traffic;

- A zoo may be wanted to relieve pressure on a nearby national park;

Unfortunately, corruption is often the hidden Black Hand affecting all the more positive remarks I will make on the design process.

In parallel with rising national economies which have engendered larger, better educated middle classes, higher disposable incomes and with global communications, and a greater exposure to the wider world, commercial developers began to see value in attractive displays of exotic wild animals, particularly in combination with other commercial developments such as resorts, theme parks, and even residential and retail developments.

Disney was not the first to exploit this potential in the West but it certainly made Asian developers sit up and take notice.

Along with following the Western model comes integration in the international zoo community, primarily through regional bodies such as SEAZA and ultimately, WAZA.

Whether commercially driven or not - and public institutions have also sought to become at least financially self-sustaining - taking on the traditional zoo roles of scientific research, conservation and education, and compliance with WAZA standards, is virtually inevitable. With CITES, the legal paths to acquiring animals for a zoo are such that cooperation with other zoos is absolutely necessary.

But that does not mean those desirous of establishing a new zoo are aware of this at the outset. A steep learning curve usually ensues.

We have already mentioned the role of government or private developers, and the regional and world zoo bodies in zoo development. Yet these are only a few of what we can call stakeholders in any proposed zoo.

Obviously, there are the visitors. The success of meeting their needs will be measured in numbers - either revenue or visits. But this is after the fact. The public is rarely consulted in the planning of a zoo but various bodies may represent them. Other government agencies, elected and non-elected officials and NGOs may have a say - and we should not neglect the actual zoo management and staff, nor I should say, the animals - but here, we are mostly concerned of course with the designers.

It is still the case that most zoo designers are based in Europe and North America and there is a steady demand for their services in Asia.

Much like the uniform shopping malls you see everywhere, zoos can begin to look all the same.

But here I want to focus on the process of getting there, and perhaps broadening at least our - designer's - outlook when working outside our own cultural frame. It is well worth both designer and client to be aware of the cultural baggage each side carries. But the burden inevitably falls mostly on the itinerant designer.

All of these are interrelated so that religious and cultural references are embedded in language. Linguists would go so far as to say that language prescribes how think, including how we think about animals. The fact that we refer to humans and animals as different categories of things exemplifies this.

All major religions have different things to say about animals and our relation to them. Dietary laws are the most obvious but all grapple with how we should treat animals while they are alive. All religions tell followers to be kind to animals and not cause them pain or unnecessarily harm them.

One brand of traditional thinking that influences architecture is geomancy, called feng shui in Chinese culture and vastu in India. Building and and site plans can be determined by placing various geometries or mandalas over them which limit where certain activities or materials can be placed according to the five customary elements. So you may be told by an owner to put water bodies in one quadrant, and caged (= metal) exhibits in another.

What this does, even without this extreme imposition but which seems embedded in our thinking, is impose a human-centrtic notion of landscape. I believe this is very deep in the human psyche. It has been pointed out that the typical urban (non-zoo) park that consists of turfed areas with sparse trees resembles the type of savannah where humans evolved some 3 million years ago. Apart from the benefit to the animals, reversing this is the rationale behind landscape immersion - to take zoo visitors out of their comfort zone. But for the very reason that it works makes it hard to persuade new zoo developers unaware of this zoo history.

At bottom is the question that science has addressed at least since Darwin: that of animal sentience. Even though scientists before and since could assert that animals don't feel pain, religions have taken the line that animals by default live in a state of grace, or in the case of reincarnation, they may gain karma (somehow) and eventually be reborn as human. Either way, humans are exceptional, have choice and so have dominion over animals, which have no choice. We can choose to exploit them, and therefore have a moral obligation to treat them ethically.

Laudable as this appears, it does lead to cultural practices such the keeping of temple elephants, keeping, feeding and release of animals in ways that are not necessarily in the animals' interest. This recent case of a sea turtle that was kept in a pond and fed coins by visitors until it required surgery is not isolated. Practises like this allow us to gain merit and / or to feel righteous but have no basis in real animal welfare.

While none of this should occur in 'proper', scientifically managed zoos, it does show what zoos are up against in educating their public. In language, culture, society and religion our dominance over and superiority to animals is taken for granted.

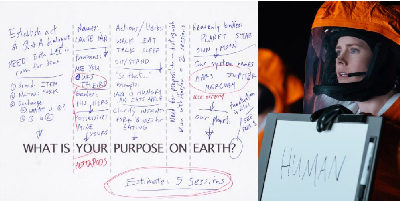

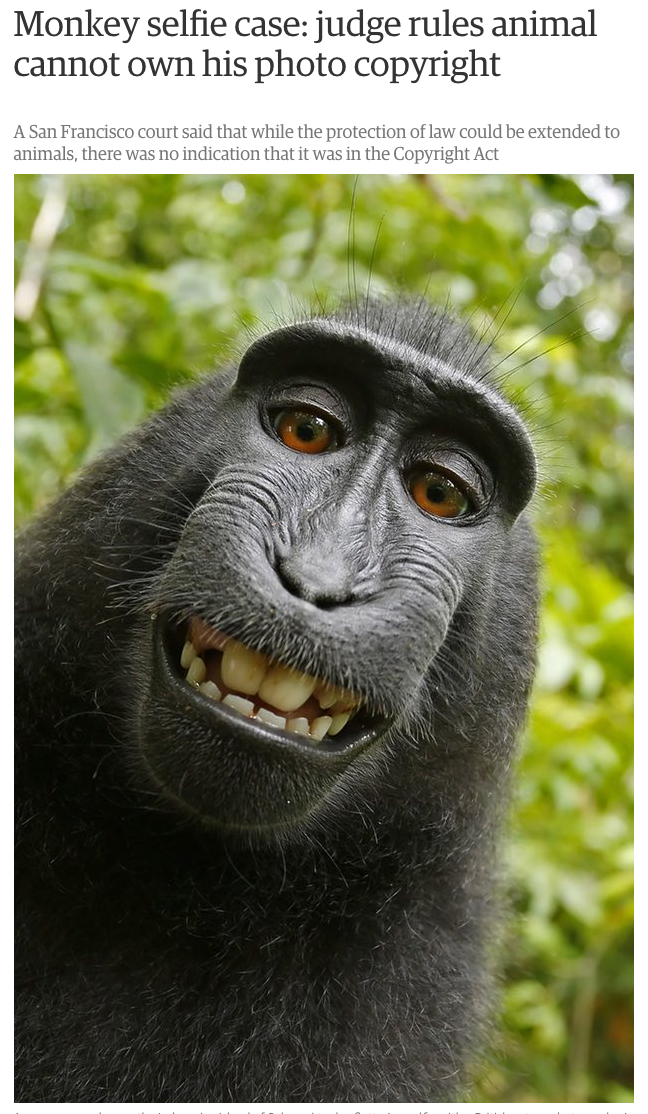

Yet the idea of animals having legal rights - as witnessed by the case of the monkey selfies - is beginning to emerge.

You could imagine future generations looking back at our most enlightened treatment of animals now in much the same way as we look back at earlier generations that denied that animals feel pain.

I will turn now to the practicalities of working in Asia, but keep in mind these philosophical issues that form the background to the work-a-day world.

When it comes to the designer-client relationship, there is obviously a wide variation in how this works in practice. However, at risk of over generalising, I'll make a few characterisations and mention some variations where significant. And not having that much experience, I am not sure how much this differs from other regions.

First, whether public or private, you often find an all-powerful figure at the top of the client hierarchy who you may be fortunate enough to meet but who often remains a mysterious presence.

Below him there may be a variety of corporate structures. There may be a project committee or a department charged with exploring the zoo idea. There may be several layers of bureaucracy before you reach the person charged with engaging consultants.

And it would seem obvious that any new zoo should involve a core management team in its design, however, the directive to deliver a 'world class' zoo given to the owner's project team typically gives no remit to hiring any high level staff much ahead of the commissioning date. And while most Western zoos would treat animal keepers as professionals, in much of the world they are simply laborers. This must be borne in mind when contemplating some more sophisticated design ideas.

Even before the team is assembled, a number of critical decisions may have been made. The site may be selected based on commercial considerations, the least of which may be suitability for a zoo. Often the least commercially valuable land is selected which may be a swamp, or steep hillside, or land fill or have shallow bedrock that cannot be excavated.

Often, a master planner may be involved in this process whose expertise is mainly town planning or commercial development.

Only then, consultants will be sought to implement the plan or its separate components. Very often this is an engineer. It may be a big, multi-disciplinary firm but often it will be the engineers that call the shots.

And there seems to be a cultural expectation for this structure, particularly in the Middle East. I mentioned the unconscious impact of language. In English, architects are often referred to as engineers. In fact according to Google, 'architect' translates in Arabic to 'architectural engineer'

I will say that with all due respect to engineers, theirs is not the best discipline to lead a zoo project. Even architects should defer to their landscape brethren in the absence of any zoo design experience.

Another reason for preferring an engineer to be the lead consultant is that everyone, from the client's management team to the officials in government agencies, tends also to be engineers.

A cultural tendency also seems to be at play here: given the stratified nature of many Asian societies, workers are not accorded high status. In the course of implementing a project, a hallowed ritual is the 'study tour'. It is common practice for higher officials to be sent abroad for fact-finding or training when often they will have little involvement in the operation of the zoo.

Apart from the professional mindset of engineers, as a zoo designer, you often deal with the absence from the process of anyone with an operational role. While it is often good to have your own preconceptions challenged, you equally would like to talk to people who know animals and can vet the details and basically tell you if it is going to work.

Given all the pressures zoo are under from animal activists, there is a risk of being seen as irrelevant in the larger scheme. With global warming, climate change, a burgeoning mass extinction, zoos may become necessary repositories and refuges for animal but they also risk becoming inconsequential. Injecting this message into technical discussions with engineers is hard.

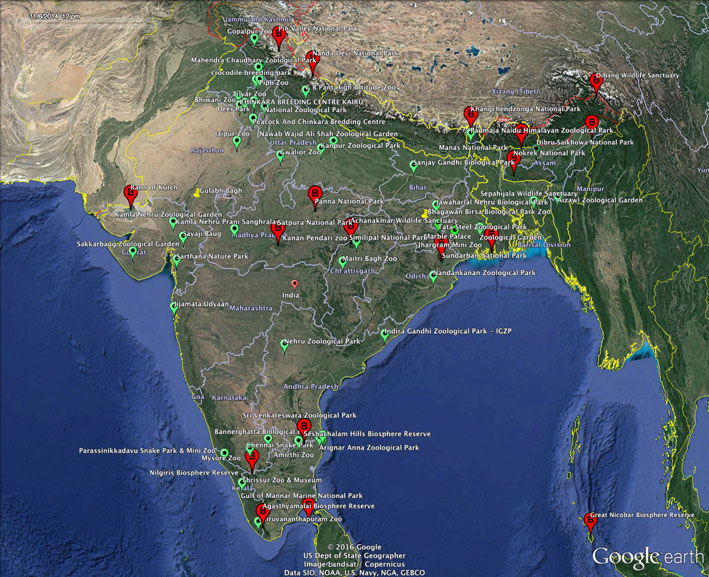

There is another type of client that you will often encounter, and this is typical of South Asia. Despite having the 5th largest number of billionaires, India severely restricts private sector involvement in zoos.

Typically, a zoo designer will mostly deal with wildlife departments, which have a much different view on things. South Asia has a legacy of small, cage-filled colonial zoos but despite this and to their credit, wildlife departments look upon sites much less than one or two hundred Hectares or so as small.

It is counterintuitive, but wildlife officers also have a learning curve in understanding how to manage animals in captivity as opposed to national parks or wildlife preserves.

Clearly, there is an opportunity in such an environment to push the boundaries of animal welfare and innovate in ways that may challenge Western experts. If only they can tap their burgeoning economic resources to finance such innovations.

This challenge is not confined to India. Yes, there are many established zoos throughout Asia that would like to develop and upgrade. However, every zoo has on top of the cultural predilections I have mentioned, its own internal culture and practices. Design consultants should be change agents but like the joke about light bulbs and psychiatrists, the zoo has to want to change.

But with new zoos, clients are often naïve about zoo design - in the nicest way. Unencumbered by established conventions or through looking at such conventions from outside, clients can ask critical questions and throw challenges at designers. This is after all how the revolutions of London Zoo, Hagenbeck's Tierpark and Woodland Park's 1970s redevelopment came about.

At the least, until the budget is burnt, or the management is hired, you as designer often have a free hand. So while you are often at the bottom of the hierarchy, paradoxically, you may also find yourself the guru, listened to earnestly. Which can be quite scary.

The best advice I can give such novice clients, which is also self-serving, is to hire the zoo director early. Zoo developers need to involve personnel who will run the zoo and who thus will have a greater concern for the details. Otherwise, for all the desire for a 'world class' zoo, and the consultant's best effort at providing one, it will fall short if a disengaged operational staff does not understand the design intent.

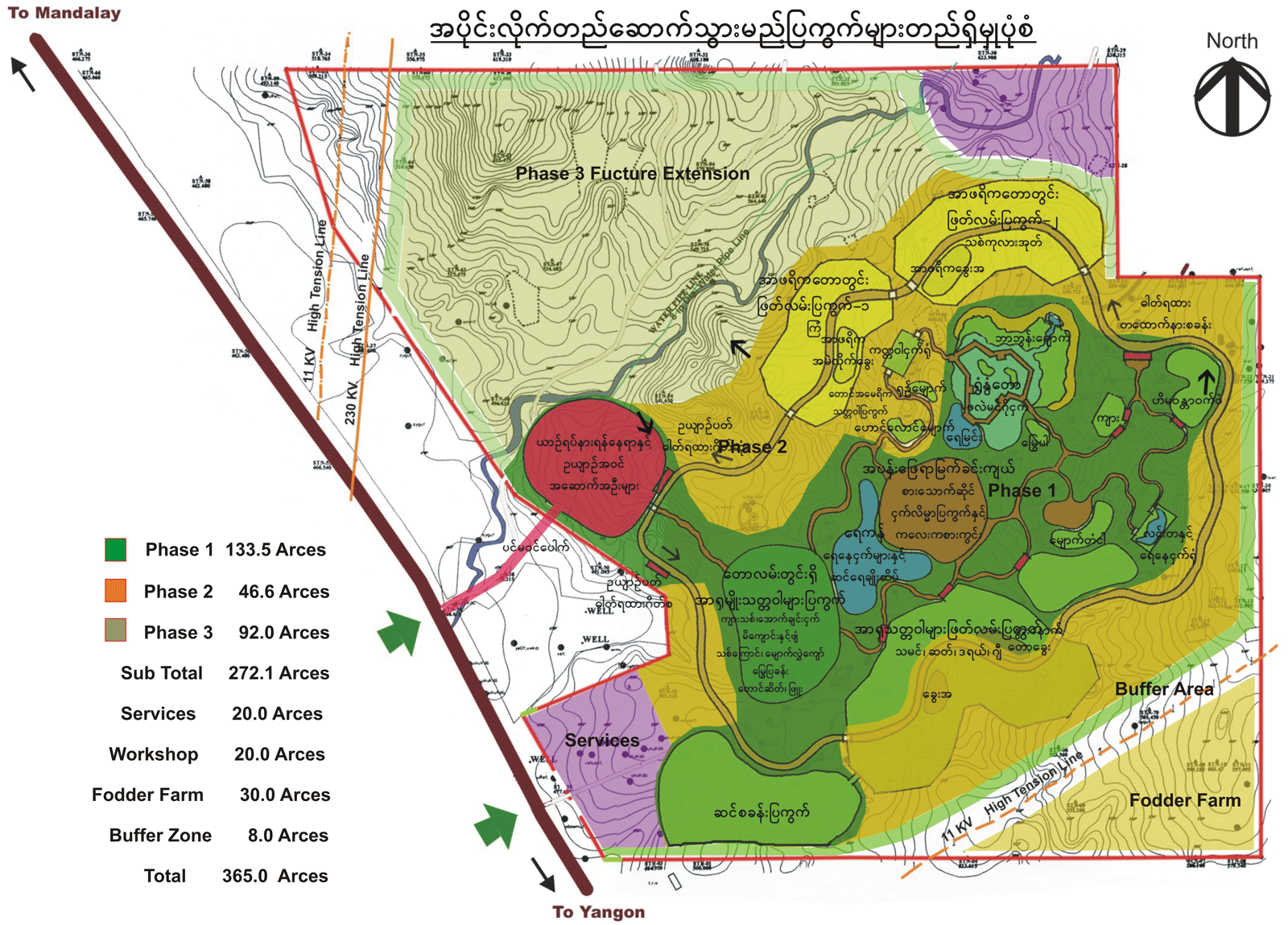

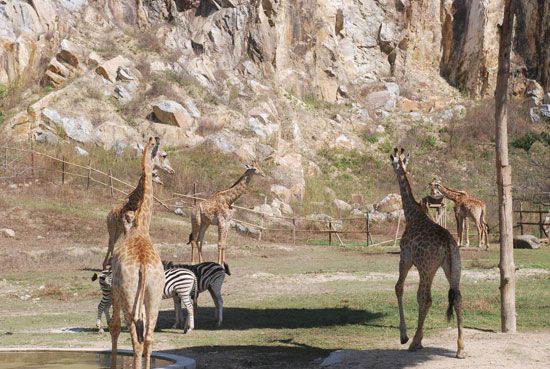

To give a few specific examples, this is a zoo opened in 2008 in the new city of Naypyitaw built as the seat of government in Myanmar. It illustrates many of the elements I have covered: a mysterious and autocratic head driving the project, a committee of army general, commercial interests facilitating it in order to curry favour, but with an Indian-style wildlife department (who all seemingly were trained in Australia in the 50s and 60s).

The result was a zoo on a site that did literally contain an abandoned quarry designed and built in six months to meet some auspicious date. I took these photos at the opening ceremony when hardly an animal was to be seen. Despite the superhuman efforts of the local team, acquiring, releasing and conditioning animals is something not even generals can decree be done instantaneously.

I believe with the fullness of time that the zoo has turned out reasonably well. Probably due to the core operational competency from the beginning, and no doubt the pressure of being literally under the gaze of the ruling elites.

This is the now defunct Doha Zoo. Its replacement is one of the projects the Qatar government is undertaking as it prepares to host the football World Cup. But the old zoo is interesting for this hexagonal geometry that governs not only the circulation but the exhibits as well. I believe the designers were British, but I can only speculate whether the geometry was imposed or inspired by Islamic traditions.

While the landscapes are basic, we found dens were often not used, in part due to the fact that even these were hexagonal. A common security feature - a master key system - had also broken down. A curator needing to access all areas should only require a single key but here, they had to carry unlabelled bunches with dozens of keys.

It would be a shame if the Islamic disparagement of depicting living things in art extended to simulation of natural habitats. However, it is likelier that there was little local input or collaboration. Meaning that while it opened in 1983, it certainly missed the wave of landscape immersion sweeping the world then.

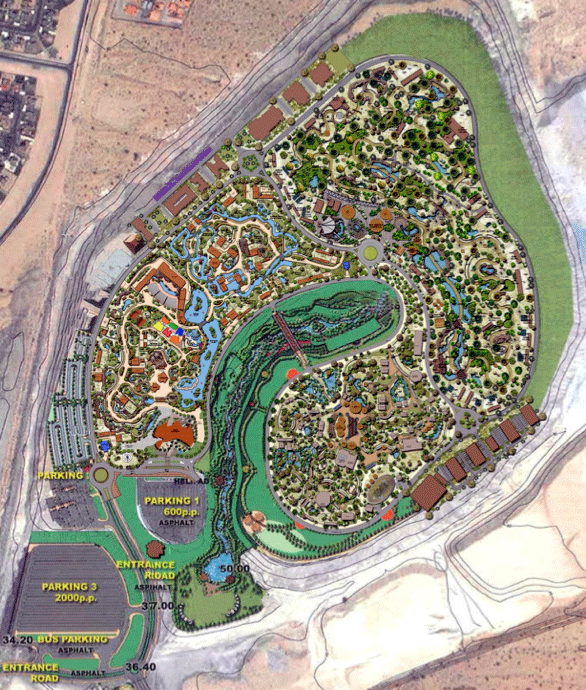

I have friends here who are actively involved in the new Dubai Safari, so I should not be too critical. The effort to replace the old, tiny Dubai Zoo has a long a vexed history and you could say the authorities finally got it right. Not in the ideal sense: many of the problems I mentioned, not least cost overruns, beset this project but it is finally being built.

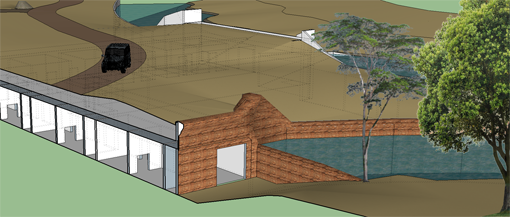

The original master plan was generated in-house by the client and the site, a 119 Ha. man-made hill of sand, rubble and construction waste, was shaped to suit the plan. My task was to develop the plan in detail.

A key element to the concept was the desire for so-called 'wow factors'. This involves trying to innovate a little but a with a lot of taking ideas from other zoos. But there is only so much you can do with design and enrichment and so on to ensure animals are always active and exciting.

The more sophisticated your design, the more expensive it often is and the greater burden it places on the staff. The design is more or less set in concrete now and so this could be a really great zoo or an ordinary or even a poor one depending on current and future management decisions. But the prospects for the first are reasonably good.

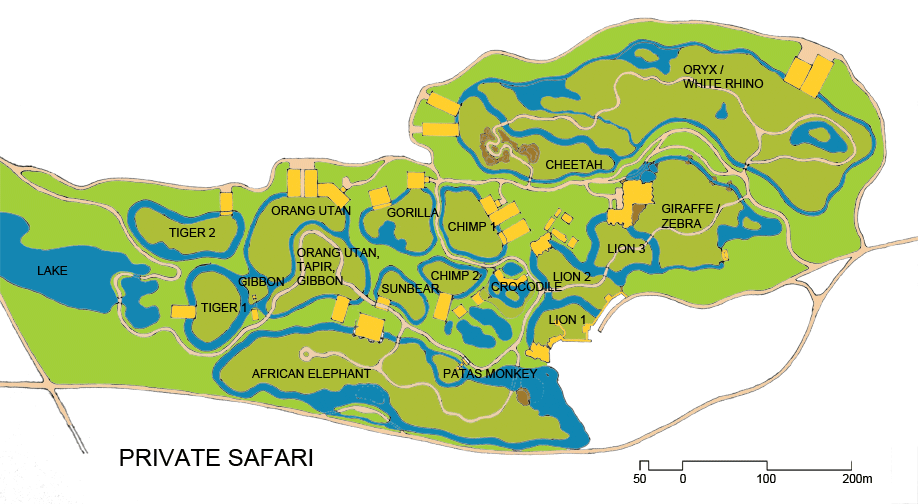

The second project is a private safari in Dubai, which illustrates again a typical pattern of top down imposition of the will of the owner. The initial brief was actually quite brilliant: the owner simply said it must 'look exactly like Africa'. Hopefully, this will set a standard in a region where, as I noted at the outset, private wildlife collections are too common but embedded in society as a reflection of an ancient tradition.

Consequent to the injunction to appear totally natural, no man-made structures were allowed to be visible, including dens and fences. Every exhibit is an island and all dens are buried or covered. All the moats are themed as water-courses and also had to be water-filled (which is not so Africa-like). But beyond these impositions, we had an almost free hand to make enclosures generously large.

Inevitably, with both these Dubai projects, the term 'value engineering' reared its head to introduce compromise. High bars were set for these projects, which is laudable and if the results fall short, hopefully that is still a good standard.

But, and I'll end with this, they do reinforce the need for greater collaboration between consultants and involvement by all the end user / stakeholder parties. This entails not only a mutual understanding between the owner(s) and designer, nor additionally, knowing who will operate the facility but it is also necessary to make assumptions on the qualities of the field staff.

To this end, and this is no small point to finish on, the back of house must be properly designed - to the best international standards, yes - but taking into account the skills level of the (yet to be hired) keeping staff. Go for spectacular, cutting edge displays by all means but determine whether the human resources of the zoo are up to making these work. Ensuring this is so is beyond the designer’s remit in most cases, but zoo designers should raise the issue constantly and at least try to determine the operational parameters and design to systems and standards appropriate to the organisation that employs them. It is a part of the designer’s duty of care to ensure their product is fit for purpose, even if it is just delivering what the client wants.

Thank you.