The Role of Architectural Design in Promoting the Social Objectives of Zoos

A Study of Zoo Exhibit Design with Reference to Selected Exhibits in Singapore Zoological Gardens

by Michael Graetz

PART 4 CASE STUDIES

4.2 Polar Bear and Sealion

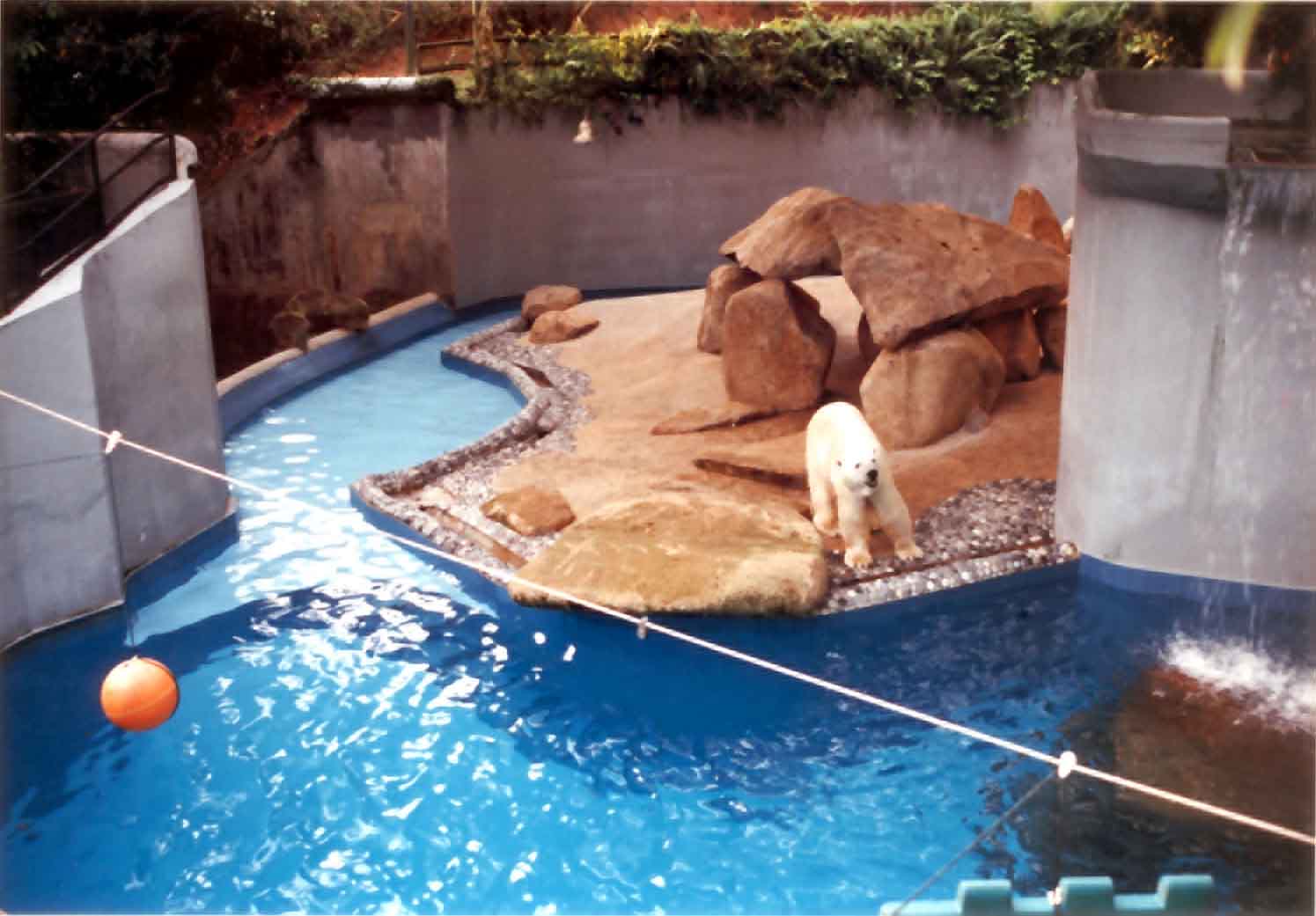

Mother, Sheba (in the water) and cub, Inuka viewed through glass

Background to the Study

Natural history of Polar bears. Polar bears, Thalarctos maritimus, are carnivores closely related to the major genus of bears, Ursus. Hence, they share many of the behavioural characteristics of other bears such as being ill-tempered, solitary, giving birth at the coldest time of year in dens dug by themselves, and hibernating through the winter.

Range map of Polar bears (Ursus maritimus), adapted from Kurt

The range of Polar bears is the arctic region to the southern limit of ice floes; however, individual bears do not make use of the whole of this area. This species range is smaller than Europe but a bear’s territory is a great deal smaller.

Polar bears hibernate and raise young on the arctic shores and islands of Asia and North America. Mothers give birth as the Polar night descends in late November to December, emerging with one to three cubs in March.

Polar bears are the most carnivorous (of a largely omnivorous group) of bears, living mainly on seals. They are opportunistic feeders, however, and will feed on carcasses and raid human rubbish tips. Opportunism is a sign of intelligence [1] and it has been observed that hunting techniques vary from bear to bear as each one learns its method from its mother.

Of particular interest is the bear's winter den. Polar bears dig through the snow into the frozen ground. A tunnel is formed up to five metres in length terminating in a chamber of about two square metres. The entrance of the chamber is partially blocked by a mound in the mouth of the tunnel.

Polar bears in zoos. Polar bears present zoos with a number of problems in housing them. Being large, intelligent, active and strong animals (up to 1.5 metres at the shoulder and males weighing up to one tonne), they demand precious space in zoos and require expensive barriers. A pool, which is the least habitat element that is normally provided, is also a costly undertaking.

There is both a real and perceived problem with Polar bears in zoos. That is the problem of overcoming boredom which is often manifested as so called stereotypical behaviour (endless repetition of a fixed sequence of movements). A strong lobby exists which maintains that the best enclosure and husbandry cannot compensate for the loss of freedom and access to their natural habitat.

This criticism concerns the internal mental state of the bears as gauged by abnormal behaviour; however, they breed well in zoos and boredom appears to be the only major difficulty in adapting to zoo conditions, even tropical. Hibernation, for example, seems to be triggered in the wild by either the drop in temperature, winter darkness, the scarcity of food or some combination of these. For they do not hibernate in zoos where they are warm, well fed and subject to a different photo period. [2] Yet the breeding season in zoos exactly coincides with that in the wild [3]. Since Polar bears are adapted to extreme cold, the difference between temperate and tropical climates is perhaps not as great to the bears as it might seem. Still, the bears face physical problems such as moulting of hair (a problem for filtration), wounds and infections, and loss of body weight. One favourable effect of climate is that the bears spend more time in the water in Singapore than in temperate zoos and hence are more active.

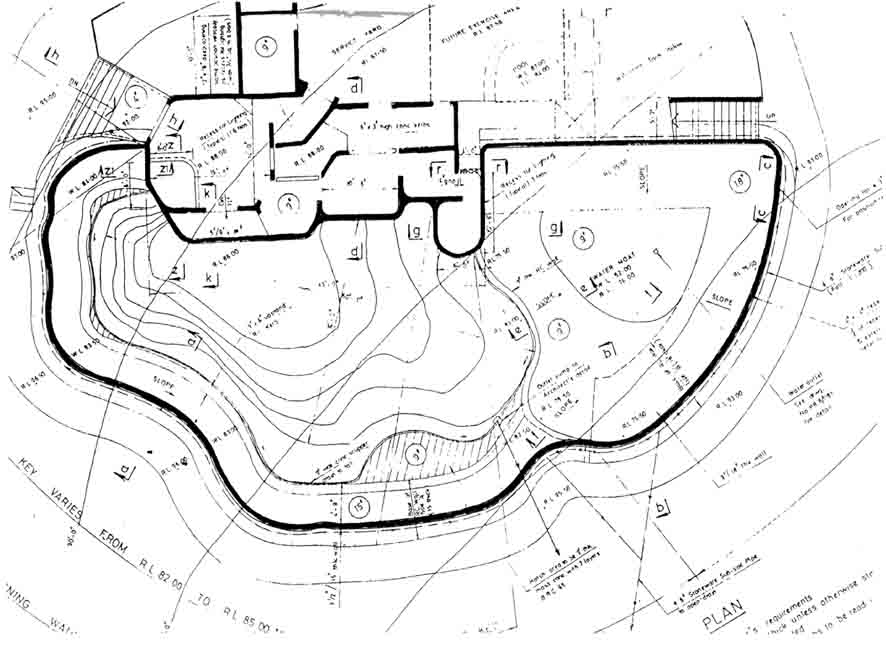

Figure 69 Plan of the original Polar Bear enclosure (drawing: CIAP)

Figure 70 Plan of the Polar Bear exhibit showing view-sheds

The original development The Polar Bear enclosure in Singapore Zoo was built in 1977 at a cost of $462,000 and renovated to its present state eleven years later at a cost of $550,000. The site is near the centre of the Zoo where the largest and most attractive animal exhibits, including orang utans, sealions, elephants and Nile hippos are grouped.

The earliest concept for the Polar Bear was an open enclosure surrounded by a water moat. The land area was to be raised almost to eye level. According to Harrison, “The landscape was to simulate a rocky shore line, and the water, . . . would cascade down from a small pool on the land into the moat . . .” Due largely to financial constraints, this and other variations on it, “. . . were finally discarded for a pit type enclosure, where the bears, although viewed from above when on land and in the water, display quite effectively.” [4] The plan of this is shown on page 153.

Climate control features included air-conditioned night quarters with a temperature of 22.7°C and 65% relative humidity; natural and artificial shade over the enclosure; the large volume (351 m³) and hence high thermal inertia of the pool which remains at a surface temperature of 24°C. The bears spend sixty to seventy percent of their time in this pool. The pit design which permitted viewing from all sides, however, inhibited air circulation [5].

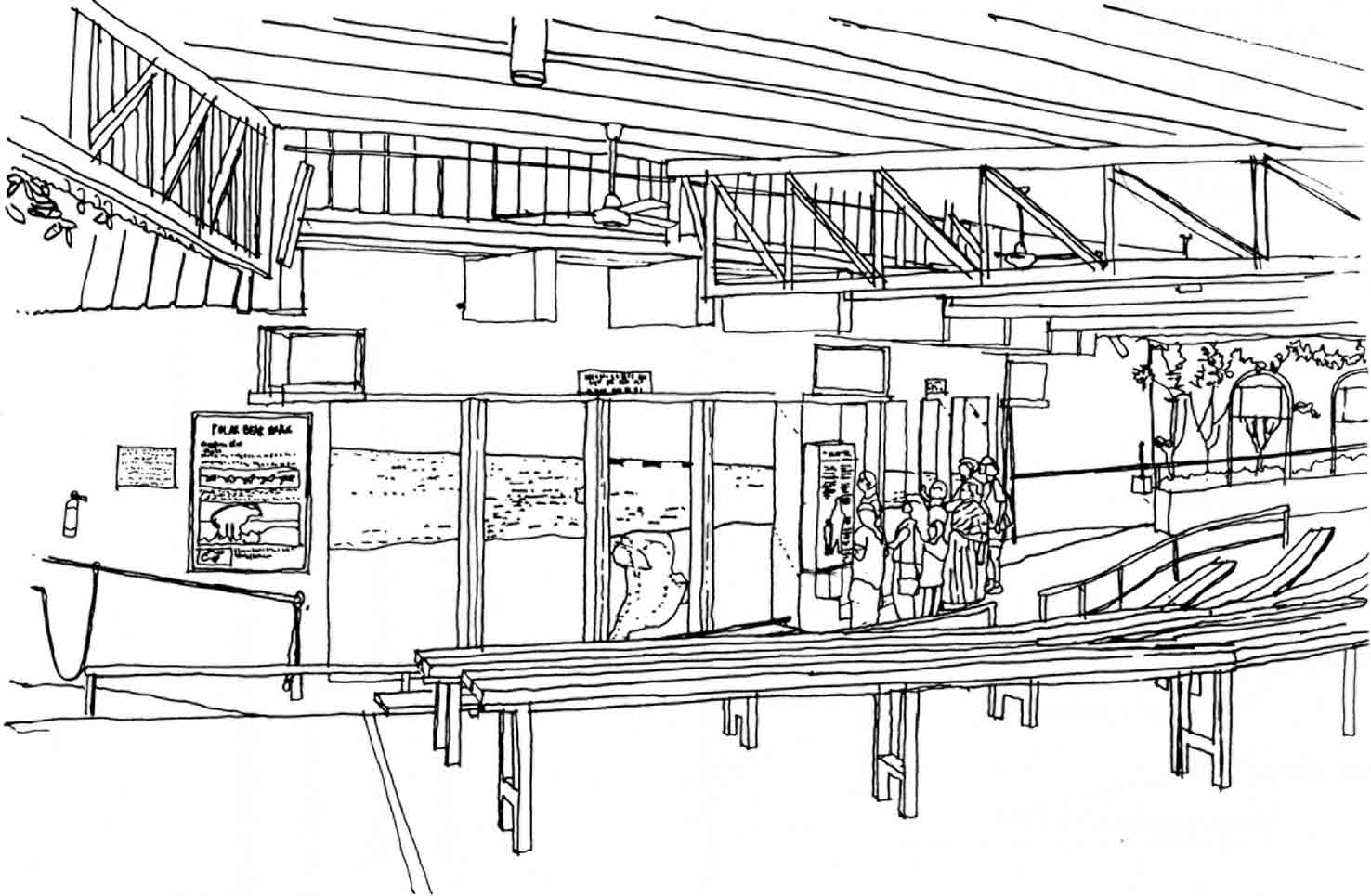

Figure 71 View of the Polar Bear Viewing Gallery

Habitat features were stylised: curved, white-painted walls and blue-tiled pool; contoured land area; a cascade and stream; and large natural boulders. The grass grown initially was soon destroyed by the bears.

A breeding den slightly larger than recommended (to mimic wild females' constructions) was planned that could temporarily be reduced in size when a mother is confined. A larger viewing den with a double glazed acrylic viewing panel was included to show the mother and cub, but was never used.

Redevelopment In the middle of the 1980's, some of the faults were corrected through a combination of underwater and dry moats viewing. The risk of a visitor falling in was a serious problem with the pit, especially as the overhang on the wall caused a blind spot directly below the viewer. Cross viewing was an aesthetic problem arising from all round circulation. Other visitors in view are a distraction and with the entire pit visible at once, viewers are constantly reminded of the bears' captivity. The psychology of the visitors’ (superior) and bears’ (inferior) spatial relation was also an inherent flaw [6]. The bears must also be under stress as, being solitary, they rarely encounter superiors in the wild [7].The renovations undertaken in 1987 required a great deal of earth moving to lower the viewpoint. The ring of the pit wall was broken and glass for underwater viewing installed. A dry moat also enables visitors to view the bears on land at eye level. These breaches of the wall has improved the physical conditions in the enclosure and provides the bears with views out. The whole enclosure is visible from the two viewpoints collectively, but not from any one point alone.

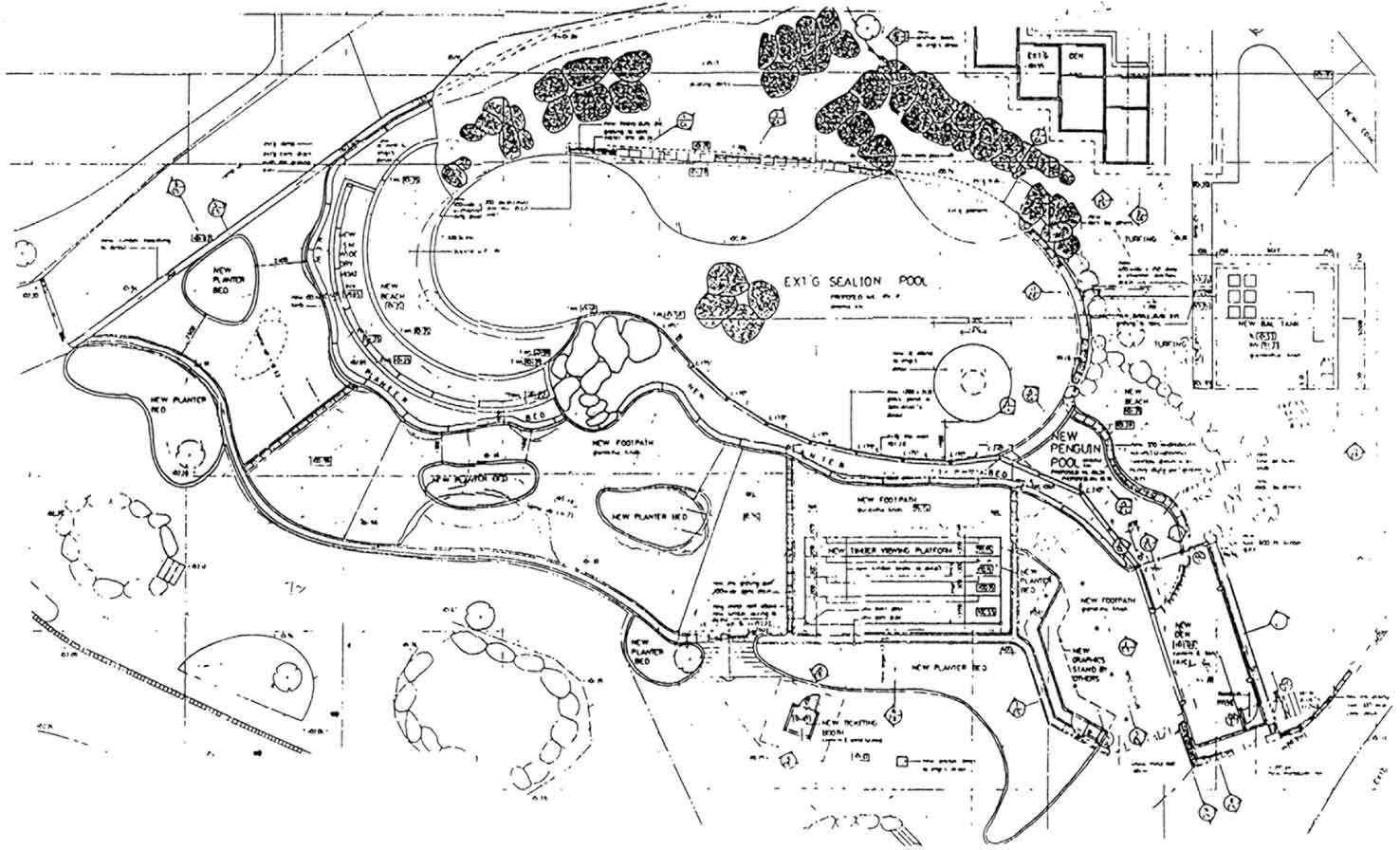

About the Sealion Exhibit. The exhibit for Californian sealions (Zalophus californianus) and jackass, or black footed penguins (Spheniscus demersus) was reopened in February 1991 after a second renovation to what was originally a bathing pool for elephants. Like the Polar Bear Exhibit, it features underwater viewing and a dry moat view but otherwise it is quite different. The back drop, and much of the foreground is treated with GFRC cast in moulds taken from rock surfaces at Labrador Park, Singapore. Rock features are extended to the public side of the glass. Wild grasses are used to simulate the vegetation of coastal California, from whence the sealions came. The pool is neither tiled or painted blue. [8]

The penguins have a section of the pool where they can retreat from the sealions; and an air-conditioned display den, into which both the pool and GFRC is continued. Penguins were mixed with the sealions in this way for several reasons. Being mixed with the sealions, their natural predators, is stimulating to both species without unduly stressing the penguins. They add the theme of ecological relationships to the exhibit, and visitors are provoked by the surprising juxtaposition of prey and predator.

Figure 72 Plan of the Sealion Exhibit at Singapore Zoo (drawing: CIAP)

Objectives and Methods

Objectives This study examines the Polar Bear Exhibit in Singapore Zoo in relation to zoo design ideas. It is compared with the Sealion Exhibit, with which it has some similarities, but comes from an older zoo design tradition. The objective was to conduct a trial post-occupancy study of the renovated Polar Bear Exhibit and at the same time compare two styles of exhibit to evaluate zoo design principles. The aim, therefore, is to assess the architectural ‘success’ of the exhibit, I. e., the effect of design on the intention of each display.

The intention in both cases is similar and translates into different levels of meaning. At the top is the desire to show the animals as impressively as possible to ensure visitors appreciate them and will be encouraged to return to the zoo in future. Respect for the animals and understanding about their habits, life history and habitat are other meanings. It is hypothesised that the sealion enclosure is richer in such meanings and, through greater interpretive and observational opportunities, ought to convey these messages more successfully.

Methods Two sets of data were collected:

- A criteria for evaluation: Zoo staff were surveyed on their general attitudes to design issues.

- ‘Are the bears happy?’: Visitors were surveyed to determine their general level of satisfaction with the exhibit and to elicit specific responses.

For the first assessment, forty one staff members, comprising twenty zoological and twenty one support staff, were asked to indicate on scales of one to ten their priorities in fourteen aspects of exhibit function and design. Their higher priorities should provide a basis for interpreting the more direct appraisal of the Polar Bear Exhibit. Differing priorities would affect both project briefs and their implementation. For example, one issue raised in the planning stages of both the Polar Bear and Sealion Exhibit was whether to tile the pools for ease of cleaning.

The visitor survey, being the first, was exploratory in nature and limited in sample size and information sought. Questions requiring simple yes or no answers with limited follow up and semantic differentials, which do not require precise answers, were favoured. This survey was later continued for these two exhibits when all four major aquatic exhibits in Singapore Zoo were compared. Here, the initial results are considered. Only English speaking respondents (about equal locals and tourists) were polled. It was hoped that semantic scales, for which visitors need only to understand single words, would also allow visitors to be polled for whom English is a second language. (See, however, the ‘Primate Kingdom’ Case Study). Hedge and Jamison [9] criticise post occupancy evaluations of zoo exhibits that assess them only from the visitors' or the animals' (but rarely the keepers') point of view. They advocate a multi-user approach. This study is no exception in that the animals were not specifically studied, but three human user groups are considered. The survey instruments used in this study are in appendix B.

Figure 73 The Polar Bear Viewing Gallery interior

Figure 74 Design aspects rated by staff. grouped by 'client' and ranked in descending order for all staff

Staff and management attitudes to design criteria. It was hypothesised that zoological staff would favour operational and animal aspects while the other, mostly managerial staff, would favour activities related to visitors. The relative priorities for the two groupings are shown on page 162 grouped by visitor, keeper and animal needs, and further ranked in order of preference of all staff.

The main conclusions are that:

- The two groups agree overall with a few major differences in attractiveness, cleaning and breeding. These differences are the reverse of what might be expected, however.

- Habitat simulation is rated reasonably well by all staff.

- Some visitor aspects fair poorly. The low rating of education is surprising.

- The three user categories--visitor, keeper and animal--are represented equally among the highest rankings.

- For all staff, the greatest priorities were (in order): animal health; visitor safety; animal needs; and keeper safety.

- The least important priorities were (from low to high): entertainment value, avoidance of stereotyped behaviour, education, and ease of maintenance.

Hedge and Jamison asked zoo directors and curators to judge the priorities of four possible user groups: visitors, keepers, zoologists and themselves. The priorities of the first three expressed each group's narrow interests. Directors and curators saw: “their own high priorities as wide ranging, encompassing nearly all aspects of exhibit performance.” [10]

The present survey asked staff with varied responsibilities to assess their own priorities. The results, however, also indicate an all encompassing view of exhibit performance. There was a high degree of agreement between zoological and non zoological staff except in attractiveness, ease of cleaning and breeding. Surprisingly, attractiveness was ranked among the highest criteria by keepers, and cleansing quite low. This may indicate a certain corporate culture--one new staff are inducted into consciously or otherwise. Either way, these attitude should find expression in the contributions managers and staff make in the design of new exhibits.

Figure 75 View of the Poalr Bear exhibit towards the glass viewing bay

Figure 76 View of the Polar Bear exhibit toward the dry moat

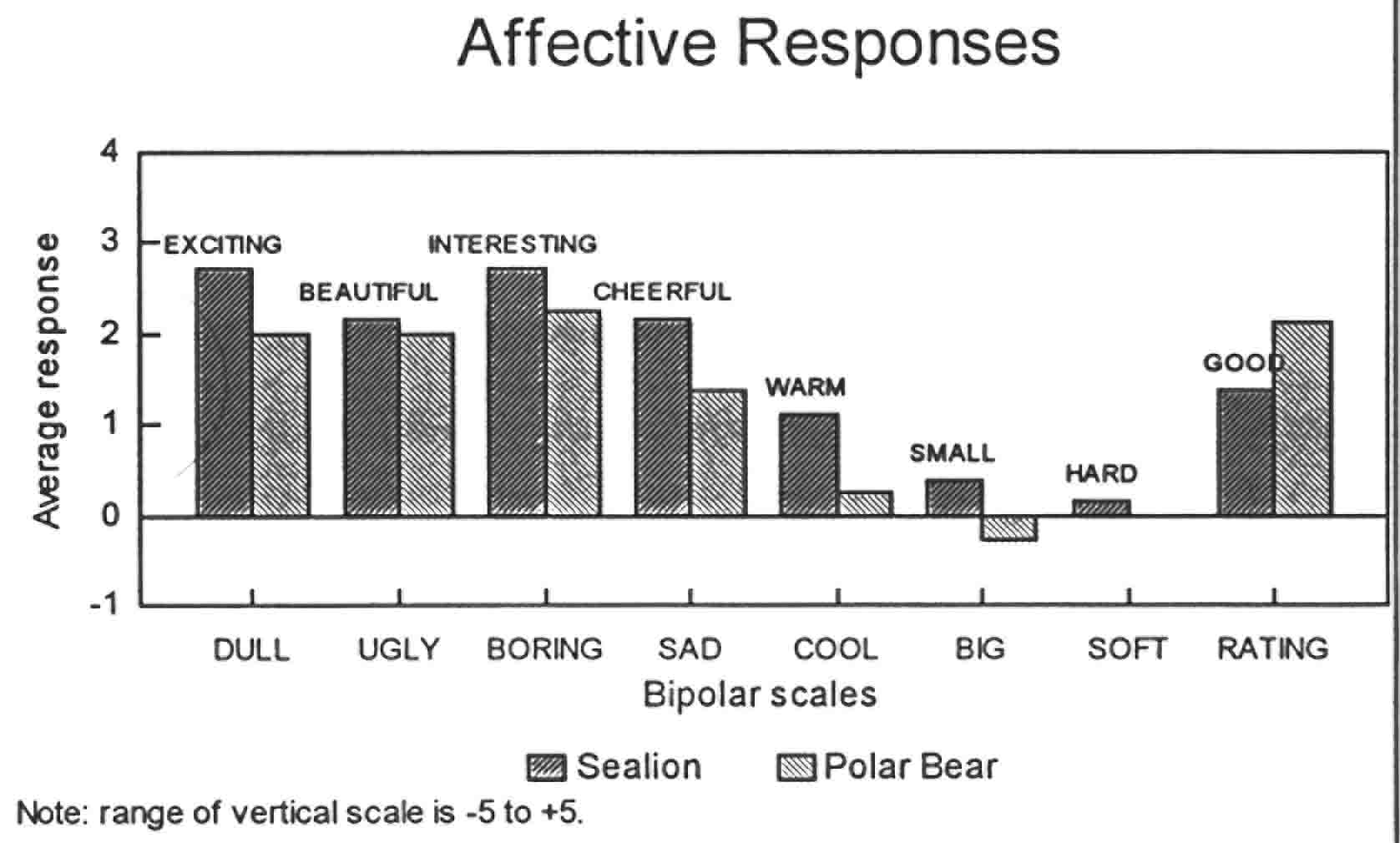

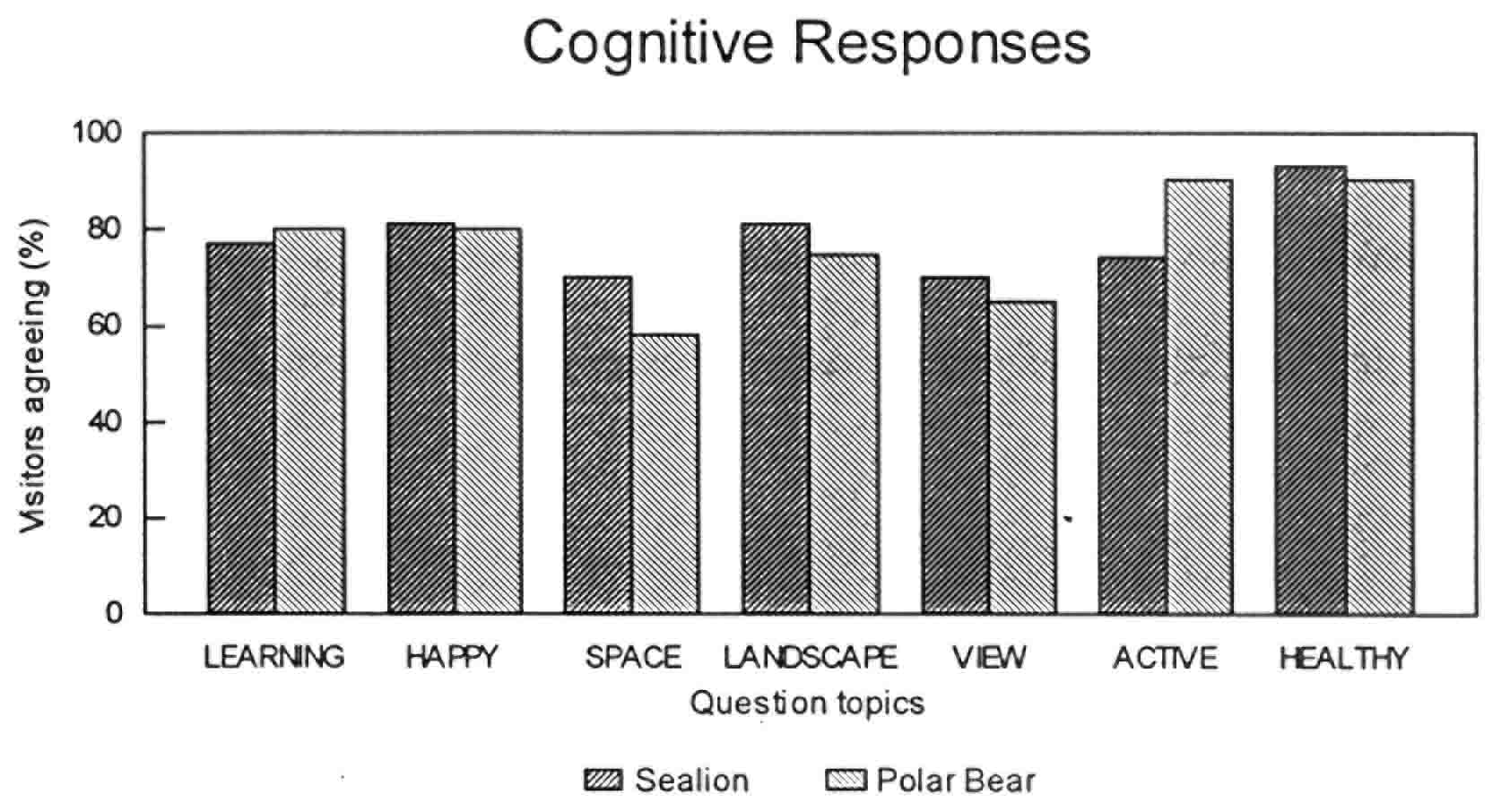

Visitor survey This first visitor survey was an attempt to find out whether the intuitive assumptions which the Zoo makes about visitors can be tested objectively. A large body of similar studies exists that this study draws upon but does not attempt to repeat, or match in rigour. [11] Specifically, this survey sought to find out whether the more naturalistic Sealion made a greater impression on visitors, enabled more learning and improved the image of captive conditions. The results are summarised graphically on page 165, 165. The affective scales all favoured the Sealion over the Polar Bear except their overall rating. This suggests that responses to questions specific to the enclosure are not as biased by the animal as was supposed. The last three scales were intended to trap respondents who may give answers they think the questioner wants.

Visitors rated both exhibits low on spaciousness and viewability. Also significant is the result that the Polar bears only rated higher than the sealions on activity. On viewing, common complaints were as follows:

- People standing in front.

- The low viewing angle (or water level too high).

- The interference from the glass mullions.

- The limited width of the view (one person asked for an all round or at least a wider view).

- The low soffit of the glass (Polar Bear).

- Clarity of the water.

- The distance of the animals from the viewer.

Figure 77 Affective responses to the Polar Bear and Sealion exhibits

Figure 78 Visitor responses to questions on the Polar Bear and Sealion exhibits

Comments on the low viewing angle most often came up at the Sealion (sitting at the front), while visitors complained about the mullions or glass proportions mostly at the Polar Bear.

Finally, visitors were asked to rate the exhibit next to all others they had seen in Singapore Zoo, on this or previous visits. The average rating of the Sealion increases when the Polar Bear has been seen previously (from +1.3 to +1.5), while that of the Polar Bear actually decreases if the Sealion has been seen (from +2.54 to +1.36). This suggests that visitors who have seen both exhibits are likely to prefer the Sealion. When their rating is unbiased by the other exhibit, the Polar Bear gets a higher absolute rating. This conclusion is based on a small sample of visitors.

Discussion

The results of this survey suggest that visitors perceive and report physical faults when they affect their experience of the exhibits, but discount them when rating that experience when there exists a strongly embedded notion about an exhibit. Thus, the Polar Bear rates lower in all aesthetic and emotional qualities but achieved a higher overall rating.

The Sealion also did marginally better in spatial measures: space, landscape and view. This may be because visitors respond to the bears--arguably the single most popular species in Singapore Zoo--rather than to the enclosure. Polar bears have tremendous crowd appeal because of their novelty in the tropics and intrinsic appeal. Churchman and Bossler [12] found visitors spent an average of 3:09 minutes viewing the Polar Bear Exhibit at Singapore Zoo compared to an average of 1:03 minutes for the eighteen exhibits studied.

Yet it may also be due to the enclosure. The Polar Bear Exhibit is all about showing the animals--explicitly. The enclosure is simply a container that was purposely made neutral rather than a realistic arctic landscape. The latter was beyond the technology then available. Thus, there is little else for visitors to react to other than the bears.

A case could be made that if the two exhibits were equalised for naturalism, the impact of the intrinsic appeal of the bears may even be reduced because of the chance of a poor view. The results as they stand do, however, lend weight to the view that visitors respond to greater naturalism and habitat simulation in exhibits. However, the intrinsic attractiveness of particular animals, or simply what they are doing at the time, can outweigh the contribution of the enclosure to the aesthetic or emotional experience. In the case of the Polar Bear, the appeal of the animal is great enough for it to stand alone. As will be seen later, animals such as crocodiles depend on their setting to overcome lack of appeal.

For staff, naturalistic enclosures are more difficult to work in and maintain, but generally, are accepted as better for both visitors and animals. In the case of the Polar Bear enclosure, there was, however, strong operational pressure to maintain the tiled finish in the pool. This was overcome with the Sealion Exhibit and it would prove interesting to repeat the staff survey in the light of the experience of servicing such exhibits since.

It is heartening that keepers show concern for visitors, as the intentions of the exhibit designer cannot be achieved without them being willing to sacrifice some operational convenience. Education, or informal learning, is one area that is apparent in needing to be linked more with the visitor experience in the minds of staff. Keepers are incidentally very much involved in educational programmes, but this does not yet translate into an important design requirement.