The Role of Architectural Design in Promoting the Social Objectives of Zoos

A Study of Zoo Exhibit Design with Reference to Selected Exhibits in Singapore Zoological Gardens

by Michael Graetz

PART 3 ARCHITECTURE AND VISITOR BEHAVIOUR IN ZOOS

3.2 Perception of Zoo Exhibits

Spatial Perception

Architects, whether by training or birth, have highly developed spatial perception abilities. This is not to say they perceive spaces differently to other people. Their abilities allow them to see new possibilities, and mould form and space into new building or urban environments; and, being an applied art, these should necessarily be understandable to the intended occupants.

Where understanding between designer and user is weak is in the meanings each ascribe to different settings. Thus, buildings acclaimed as masterpieces may not work for the user; and buildings said to be architecturally flawed are sometimes redeemed by their occupants' liking of it. Space is therefore not immutable and has different meanings for different people. Architects are of course aware of spatial meanings and its variability, but the question is whether they, as a group, are aware of how building users, perceive their environment. Especially when architects work at a remove through institutional clients.

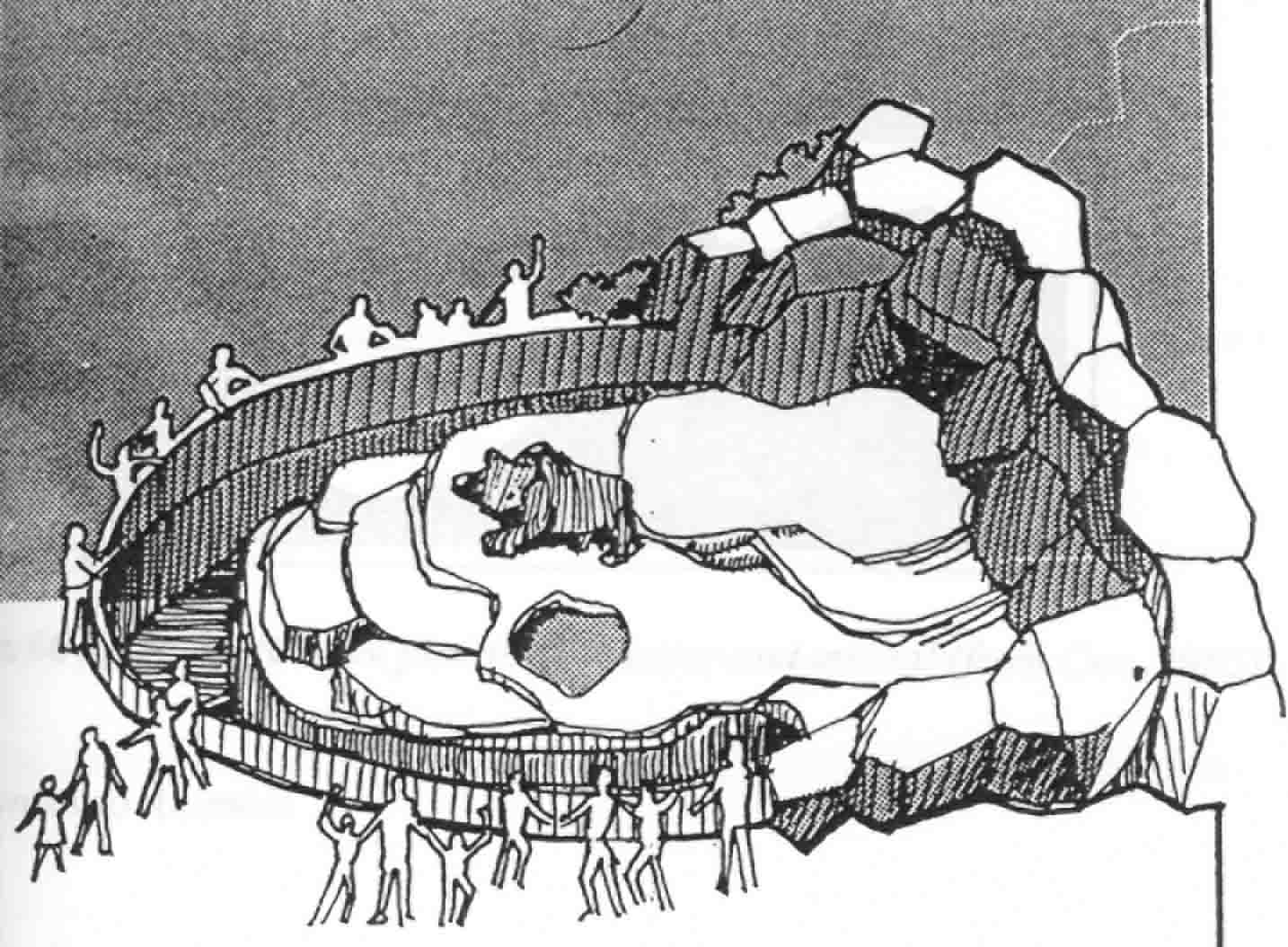

The answer lies in the slow cross fertilisation taking place between architects and environmental social scientists. For example, Polakowski refers to the work of theorists in discussing spatial illusions which are presumably intrinsic to humans, or at most may be cultural. One such is the idea that a circular exhibit has a centripetal character and so, attention is drawn to the centre. He advocates using such visual illusions to enlarge exhibits and control where visitors’ attention is focused [1]. The effect of spatial arrangements on social interactions is more abstract and difficult to observe, but is at the heart of general criticisms of modern architecture.

Perception of Meaning in Exhibits

Perception in general is a cognitive process in which viewers of a scene attempt to ascribe meanings to it, to make sense of it. It is often described as an attempt to bring one's self in to equilibrium with novel environments. Such perceptions are far from literal and will have a high emotive content. Kaplan and Kaplan discuss the human response to landscape and observe:

Aesthetic reactions thus reflect neither a casual nor a

trivial aspect of the human makeup. Rather, they provide a guide to

human behavior that is both ancient and far reaching.

Underlying such reactions is an assessment of the environment in

terms of its compatibility with human needs and purposes. Thus

aesthetic reaction is an indication of an environment where

effective human functioning is more likely to occur. . . .

Such a position does not require that people are

necessarily aware of their needs or that preferences be universal.

The way preference feels to the perceiver stands in sharp contrast

to the process that underlies it.

[2]

It may seems that the individual's experience is therefore unique--to the despair of the exhibit designer--but Kaplan and Kaplan go on to point out, there is a commonality of human experience that can be drawn upon:

. . . what are the categories [in experience of nature]? Given the lack of training in appraising the environment, one could expect the categories to be idiosyncratic and as different as people are different. This has not proven to be the case. Rather, we have found strong commonalities in these categorizations. [3]

Knowledge must, however, be accumulated over many studies before the effect of specific factors can be said to have been isolated.

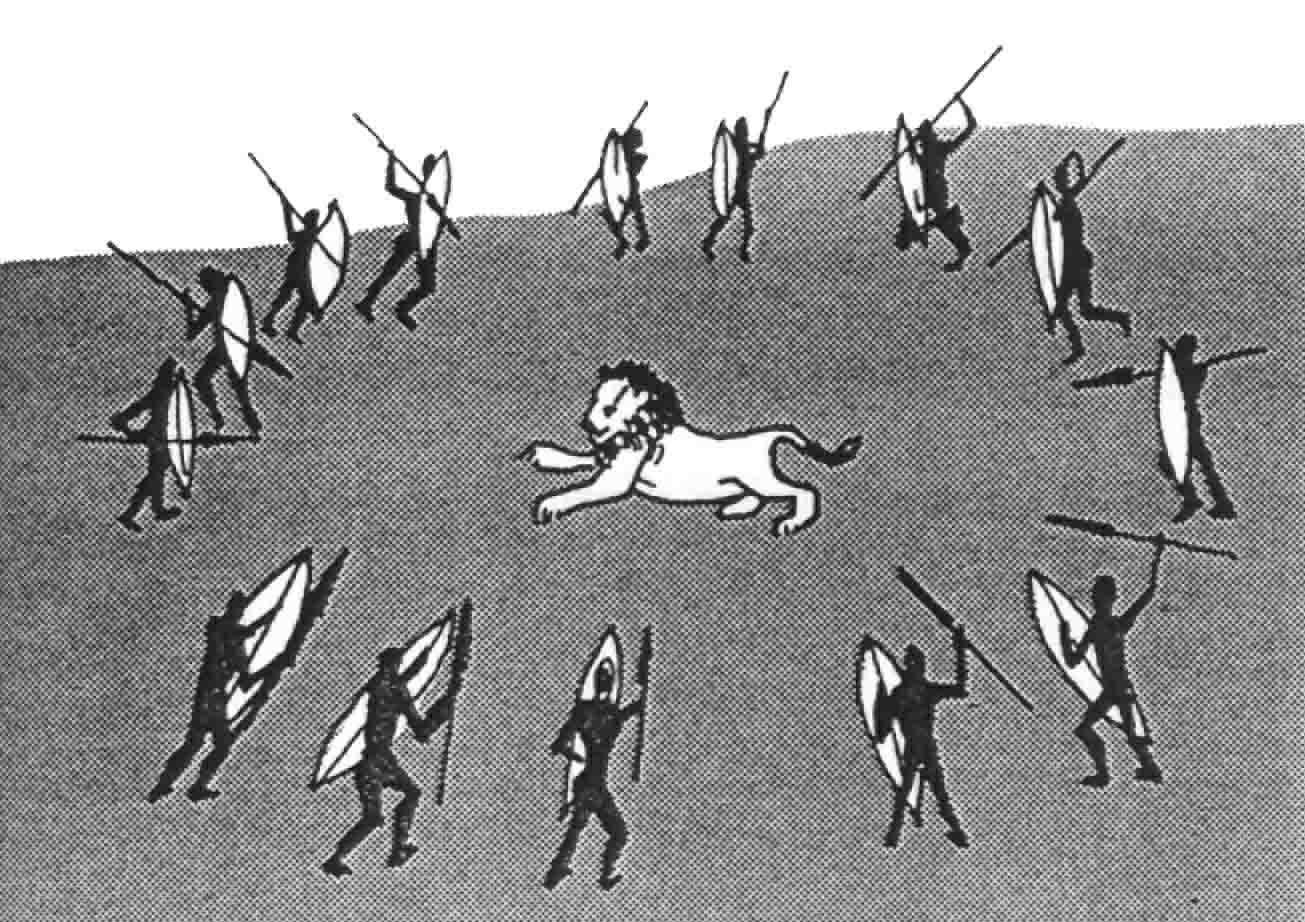

Fig. 65 Situations where humans dominate animals (from Coe, 1985)

Ruddell et al. [4] discuss the perceptual factors, and theoretical explanations, in people's assessment of scenic beauty. These are divided into cognitive and affective categories. Cognitive theory is concerned with the information a view presents and in this context, beauty is correlated to a preference for information rich environments. An environment may thus be considered poor due to barrenness or screening (e.g. by vegetation).

Cognitive process follows a set pattern: visitors enter a new environment and immediately try to make sense of it. The next step is a desire to seek more information, or to become more involved. Thus, they are looking for a certain amount of complexity, sufficient to interest them, but with enough left unsaid to entice them on.

Simultaneously, visitors respond emotionally to what they see. In fact, it is believed that the emotional reaction occurs before any intellectual response to the scene. Humans are said to be constantly attempting to come into a new equilibrium with the environment in response to changing circumstances, i.e., to enhance their state of well being. Thus emotive factors decide initially whether a visitor will be drawn to an exhibit or pass it by.

Fig. 66 Effect of relative position of visitor and animal (from Coe, 1985)

Responses to Animals

Few studies has been made specifically of visitors' responses to animals, or, as has been noted, how these can be modified. How much are responses to animals culturally or otherwise fixed and how much are they influenced by the exhibit? Coe [5] lists eight human psychological traits and suggests they are at play in zoos which have been noted as pointers for further research. These are:

- Intense attention will be given to any potential threat or danger, such as a seemingly unrestrained wild animal in a zoo.

- Out of the ordinary experiences will be memorable.

- First impressions form more permanent attitudes which can be carried through life.

- Our respect for human leaders often derives from their dominant position. This applies to zoos in attempts to prevent visitors feeling dominant over animals.

- Anthropomorphism places unwarranted human characters on animals. Again avoided by reversing dominance hierarchy of visitor and animal.

- Ambiguity and contradictory sensory stimuli lead to wrong conclusions or missing the overt message.

- People are more receptive when they are enjoying themselves. A part of the positive sense of excitement is an element of fear or risk taking.

- People’s ability to suspend disbelief can be broken by inconsistencies in the ‘reality’ and elements that do not belong.

These are put forward as hypotheses and are suggestive of common sense in some cases. Finlay et al, do find in support of this that “the perceptual context . . . must be totally free of contradictory clues” [6]. Much is made of concealing barriers, raising animals above the visitors, and total realism to achieve these responses. It is difficult to accept that anthropomorphism is expressed as dominance, however. This is usually associated with conscious attitudes, such as that monkeys are mischievous, which are often cultural. Animals as servants is less of an anthropomorphism as a reality.

The ‘Primate Kingdom’ case study later in this dissertation points to the danger of using ‘danger’ to create a vivid impression. Respondents in Mandarin expressed a similar degree of arousal to the English sample, but they gave it a negative association. Verderber et al [7] found that the ambiguity of concealed barriers can make elderly visitors perceive the zoo as a threatening environment. But their study, in obtaining this result, does offer evidence for success in achieving the perceptual aim of such barriers.

On the other hand, visitors to ‘Primate Kingdom’ showed no apprehension about the animals ever escaping. They could not cross the wide water moats, so anthropomorphically, it is assumed that they are safe from the monkeys. The case studies also show that the most memorable exhibit is the Polar Bear. It is clearly quite a complicated equation.