The Role of Architectural Design in Promoting the Social Objectives of Zoos

A Study of Zoo Exhibit Design with Reference to Selected Exhibits in Singapore Zoological Gardens

by Michael Graetz

PART 4 CASE STUDIES

4.3 Pygmy Hippo Case Study

Background

The under-water habitat display for pygmy hippos (Choeropsis liberiensis), which was opened to the public in April 1993, was the first ‘habitat’ type exhibit in Singapore Zoo designed by a foreign designer [1]. The experience resulted in an injection of new ideas and technology, but not without difficulties. Local consultants and the Zoo itself applied two decades of nearly independent zoo design experience while gaining knowledge and experience in the new zoo-design development techniques, and project documentation, that originated in America over the same period. The imported skills involved, in addition to design technique, different standards of specifications and supervision for the work.

The Zoo developed an initial brief covering the site; animal mix; display concept and theme; and animal, keeper and visitor needs. The end product diverges and departs at a tangent from the brief in some unanticipated ways, but this illustrates well something of the way a design evolves; that in reality even dogma cannot be immutable. The design met the essential requirements as set out in the programme.

The following paragraphs briefly describes the concept, and the exhibit itself, as it evolved to become.

Concept. A riverine theme, intended to be geographical (West Africa). The Zoo changed this to a generic riverine habitat for pragmatic reasons (unavailability of some species of fish and mammals). The Pygmy Hippo view has scenes typical of the habitat niche (river-to-forest), of this species, i.e. the riverbank.

As mentioned, visitor and animal areas are not visually integrated. The contrast of the habitat areas with the human areas conveys the idea that the proper environment for hippos is very different from human environments. This is reinforced in the outdoor immersion type exhibit for duikers (with an overlook for the hippos).

The gallery contains a series of views into a river, showing river bed/bank, symbolically following the downward course of the river, but not literally flowing. So there are no cascades between tanks, which are separate scenes.

A separate enclosure was created specifically for tram passengers to see from the tram road. An artificial tree trunk frames the glass view, and twin eroded earth banks at the sides. The tree has seemingly fallen across the embankments and conceals the top of the physical glass frame.

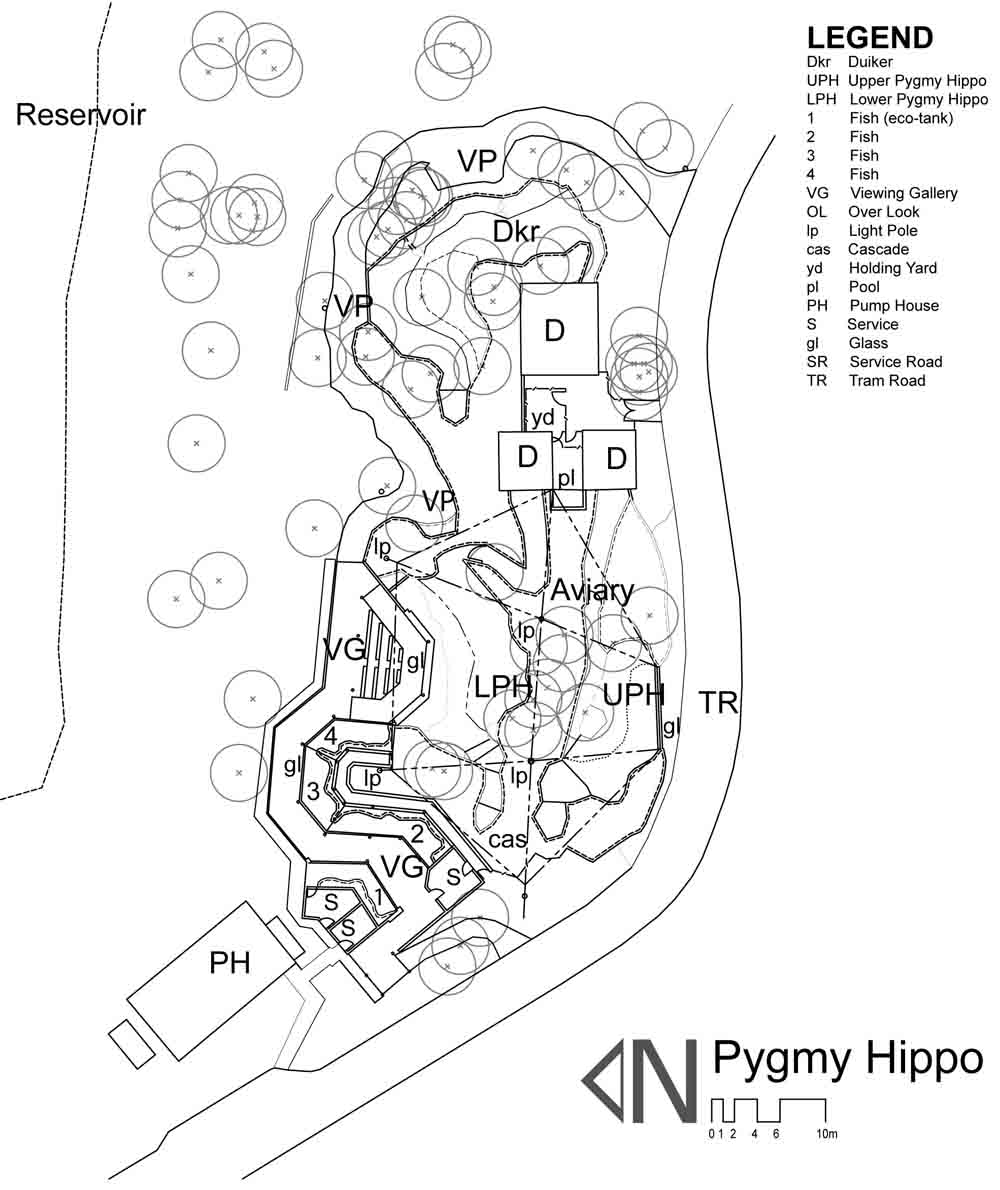

Figure 79 Plan of the Pygmy Hippo Exhibit

Building structure and materials. The viewing gallery is deliberately artificial, manmade, industrial. Steel, glass, glass block, and vinyl flooring were used extensively in contrast with the studied naturalism of the habitat.

In the habitat, extensive use was made of ‘Gunite’ and Glass Fibre Reinforced Cement (GFRC) rockwork. For the pools and tanks, the most critical area is the water-retaining system. ‘Gunite’ was used as an aesthetic treatment and to shape the forms required (mud bank, etc.). It should be (but was not) divorced from the primary waterproof barrier and considerable effort was required to seal leaks. ‘Gunite’ is a site-mixed concrete and the same degree of quality control as ready-mixed concrete cannot be ensured. Like-wise, glass installation (laminated, tempered) is an area requiring specialist expertise.

Aviary. The conversion of the two hippo enclosures into a single aviary was achieved simply with free standing poles up to ten metres in height supporting steel cables and polythene bird netting. Control of sight-lines avoids disturbance of the naturalism by the netting.

Planting. This was integral with the design. (Though obvious sounding, when plant growth is so rapid and quickly becomes attractive in the tropics, it is easily ignored in planning). Trees form a forest canopy background to the hippos and duikers; grasses and aquatic plants simulate the river edge. Dead (real) wood was placed for perching birds and overhanging plants for shade (an important consideration when using large concrete surfaces in a hot climate).

Although the strict geographic theme was later given up, it is worth mentioning that consideration had been given to the African theme in planting. Where actual African species were not available, local ‘simulators’ or allied species were used.

This exhibit is architecturally, as well as in landscape terms, a departure from earlier developments. Commonly, structures are considered a necessary evil and are either concealed or an attempt is made to harmonise them with their simulated environment, i.e., to produce vernacular style buildings in keeping with the geographical theme. The strategy of concealment was applied only to the animal and service buildings (i.e. dens and the large pump house). The naturalistic displays have also been taken a step further in the realism of the simulated habitats.

Figure 80 Under water view of pygmy hippo (Hexaprotodon (= Choeropsis) liberiensis)

Figure 81 Over water (glass) view of pygmy hippo

Biology and husbandry of pygmy hippos. Little is known of their habits in the wild. Unlike the Nile hippo, which is a herd animal of large water bodies and grasslands (and easily observed), their pygmy cousins are solitary forest dwellers. They tend to spend the day in water--like the Nile hippos--and forage away from the water course by night. In Singapore Zoo family groups have been kept socially, though fights do occur. Their ability to coexist generally has been taken advantage of to present more attractive displays with births taking place regularly.

They are herbivores, and in the zoo are given fruit, vegetables, grass and prepared herbivore pellets. The design significance of this diet is what come out from the other end! Observation of the hippos' defecation on a zoo diet showed that the faeces are not as fibrous as might be expected. There are two components of hippo waste so far as filtration is concerned: particulate and fibrous material. Strategies for both were adopted in the design of the mechanical systems for the new facility, i.e. large sand filters and ozone (for sterilisation) coupled to both surface skimmers and bottom drainage with high capacity pumps to ensure a rapid turnover rate of less than an hour.

Objectives

The Pygmy Hippo Exhibit can be classified as a “fourth generation” exhibit, as described elsewhere in this dissertation. Given this and the educational and experiential design objectives, it is useful to examine:

- Whether going for a high impact exhibit actually increases informal learning among visitors, i.e., what messages does it communicate?

- Whether there are any perceptual problems with the exhibit or habitat simulation?

- How does it compare with the other under-water viewed exhibits in the zoo?

Previously, exhibit design influences from other zoos could be said to have been filtered to meet local needs and concerns. With the more direct importation of such influences, it can be asked to what extent does the design of the new exhibit address local needs as opposed to peers in the zoo and zoo design fraternity. A cultural theme inevitably runs through any study of design in Singapore, as well as themes arising from social and climatic contexts. Therefore, the question of whether the aesthetic, intellectual and perceptual principles incorporated in the design have a local validity or are universal is investigated.

It is not likely that visitors will be consciously intrigued by, or aware of the concepts behind the exhibit design, but rather they will react in unconscious ways to visual and other perceptual clues (aural, spatial, etc.). These effects can often be fortuitous but it would be interesting to determine the factors, whether in the details or in the conceptual framework, that govern the responses of visitors; whether, for example, the environment for the animals increases their activity and so, engages the visitors' attention; whether a more interesting visual display which compensates for any lack of activity on the part of the animals is just as engaging; or whether the engagement of visitors necessarily means they are interpreting the scene in the ‘correct’ way.

Methods

To test the educational value of the two displays, it is necessary to determine what sort of impression they make on visitors and how much they learn. Two visitor surveys form the basis of this case study.

- Visitors were questioned on their subjective attitudes to the exhibits, their prior knowledge of the exhibit and on what they may have learnt from viewing them.

- A similar survey instrument to the Polar Bear study was applied. It was modified to improve its administration and to enable comparison with three other under-water exhibits in Singapore Zoo.

The first questionnaire to test visitors' knowledge and attitudes is simple--questions like: the name of the animal; where does it come from; what it eats--information available from the graphics and about as much as is conventionally hoped visitors learn. A few questions requiring value judgements were asked, such as: would it matter [to the visitor] if these hippos died out in the wild? Questions about the animals rather than directly about the enclosure were asked to gauge the degree to which the enclosure biases visitor responses to the animals both in terms of what they learn and how they stand on conservation issues.

In order to distinguish any such effect, the primary target group was polled as they exited from the main viewing gallery towards the secondary duiker exhibit. Visitors were also polled going in the opposite direction before they had seen the hippos. The latter formed a control group uninfluenced by the display they were about to see.

Correlations were thus sought through these surveys between the design intentions for the visitor experience and what visitors really make of the architecture and animals, i.e., do visitors appreciate or understand these intentions; are they favourably influenced by them?

Results of the Surveys

Survey on learning and conservation awareness Of all surveys conducted for this dissertation where one group is compared with another, the set of data from the two groups in this survey produced the most striking differences. When asked about the geographical origin, habitat, swimming ability, diet and endangered status, visitors were more likely on every question to be reasonably correct after seeing the exhibit. These results are summarised in Table IV.

Table IV MOATED EXHIBITS IN SINGAPORE ZOO

QUESTION |

CONTROL |

SUBJECTS |

|---|---|---|

1. Origin |

12.5% |

45.5% |

2. Habitat |

50.0% |

70.8% |

3. Swimming |

75.0% wrong |

79.8% right |

4. Diet |

56.3% |

70.8% |

5. Endangerment |

50% |

62% |

In most instances also, the subject group were more sure of the answer even when it was wrong--the number of null responses is much lower. These questions were followed by two concerning the respondent's attitude to the potential extinction of pygmy hippos. The first asks visitors to express their degree of concern at this possibility. Again, a much higher value was obtained from the subjects, 7.83 against 5.38 (median values out of ten).

The next question was intended to see whether visitors would transfer their concern on to the wild population, given that hippos are not likely to disappear from zoos where they breed well. The hippos in the wild are in a far off land and if they did disappear, the fact would hardly affect people's daily lives. To express concern in a poll of this nature is easy since the respondents are not being asked to do anything about any perceived threat to wildlife. Therefore the result should not be taken too optimistically.

What is interesting is again the apparent effect of seeing before them the real potential victim of an abstract concept like extinction. Of the control group, 56.3 percent would be concerned at such a calamity. Interestingly, this is close to the average (mean) scalar response of 5.9 to the preceding question, i.e., this group was 59 percent concerned at possible extinction. Of the subject group, 87.5 percent expressed concern at only being able to find hippos in zoos. Possibly, however, if questioned a half an hour later, the percentage could well be expected to drop again.

Figure 82 Pygmy hippo tram view with artificial tree hiding the glass top frame

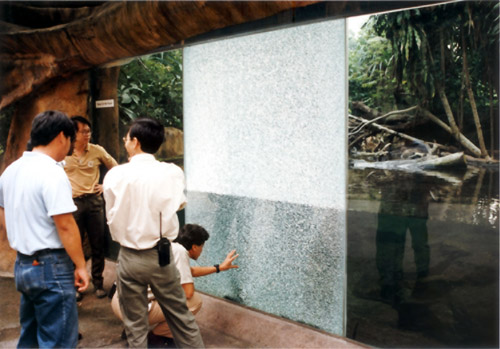

Figure 83 One disadvantage of glass viewing - the inner glass lamination did not shatter and still holds water, however

Finally, four scalar type questions were posed to gauge how visitors feel about zoo visits as educational experiences or opportunities. The first asked visitors to rate themselves as frequent or infrequent zoo goers to see whether frequent visitors have more enlightened attitudes towards conservation. The control/subject averages are similar at 3.2 and 3.8 out of ten respectively, differing by just six percent, although the median values diverge by twice as much--2.0 compared to 3.3. The absolute average frequency of visits by Singaporeans is about once in three years.

However, no correlation between this and the aim of learning was found. If anything, more frequent visitors are more likely to say they come for pleasure, even when prompted that they might consider it to be educational for their children. The control group at 5.1 had no strong feelings about coming for learning or enjoyment while the subjects, at 3.8, or 24.0 percent off the neutral score, were positive about enjoyment. Perhaps this is due to the experience of viewing the Pygmy Hippos. Learning may never-the-less still take place unconsciously.

The final two questions ask to what extent visitors learn about animals through the zoo and whether the zoo raises their level of conservation awareness. These elicited mean scores in the six to seven range for both groups--rather disappointingly for the educational objectives of the exhibit. However, there was less unanimity in answers from those who had yet to see the exhibit.

Survey of responses to the exhibit More is made of the results of this survey in the case study of under-water viewed exhibits; however, the main results obtained for the Pygmy Hippo Exhibit are mentioned here to relate them to the foregoing survey results. The simple results show that visitors are extremely positive about the animals--they are considered healthy and active--but more circumspect when it comes to the facility.

The view of the hippos received the highest (virtually unanimous) approval rating among all similar glass fronted displays. The next best result comes from the landscaping; 79.1 percent agree that it is well done. Less agreement existed on the well-being of the animals at 69.8 percent. Lastly, the lowest rating of all: a minority of 48.8 percent of respondents believe the animals have enough space.

The Pygmy Hippo was rated best of the under-water exhibits by nearly a quarter of visitors questioned at all four exhibits. At other exhibits, the Pygmy Hippo competes best at the Sealion, being nominated as best by 21.4 percent.

The semantic differential scales show a tendency to the middle, somewhat toward ‘positive’ aspects except for the ‘SMALL-BIG’ scale on which the average response was 4.73, favouring “SMALL” by 5.4 percent.

Such ambiguous scales were included to avoid stock answers. Responses to adjectives such as “HARD” and “SOFT” are taken as affective judgements even when the visitor takes it literally. This is evidenced by the fact that the two most similar exhibits in habitat simulation--the Pygmy Hippo and the Crocodile--rated 5.1 and 3.47 respectively (“HARD” is zero). This must therefore reflect an emotive response to the animals more than to the habitat.

On emotive scales generally, the Pygmy Hippo Exhibit rated reasonably well. Against “SOFT”, “WARM”, “BIG” and “CHEERFUL”, it averaged 5.84, just ahead of the Polar Bear at 5.79. On scales designed to capture more direct reactions, i.e., “ATTRACTIVE”, “BEAUTIFUL” and “INTERESTING”, the first two could be regarded as synonyms, but “attractive” is the preferred description; however, the third aroused an even greater response at 7.44. The three scales combined produce an average of 7.02.

Discussion

The three objectives stated for this study relate to learning, perception and generally comparing the exhibit with others of the same under-water type. One component of the study examined what visitors learned and how their attitudes were changed by the exhibit; the other studied the environmental factors that may or may not dispose visitors to be improved by the experience.

The first survey showed a remarkable amount of learning occurs, while seventy nine percent in the second survey said that they had learnt something. There is also evidence for changed attitudes though, the visitors do not seem to be aware of it in themselves; which is perhaps a good thing. The second survey also shows that there is a problem in perception--or rather, a negative emotional response to the way visitors perceive the exhibit.

Comparison with the three other exhibits reveals that the hippos rank third, ahead (albeit, well ahead) of only crocodiles. This may partly account for responses to the animals' environment coming more to the fore. Pygmy hippos are even less well known than their larger Nile relative, which are not portrayed in visual media as well as Polar bears or sealions. Most representations (an exception is in Disney's “Fantasia”) show them submerged, as they are most often seen in the wild. In a sense, then, hippos are suited to a discussion of ecology and habitat as visitors are less influenced by preconceived ideas and images.

As mentioned earlier, the exhibit graphics were kept simple on the theory that visitors are put off by verbose and complex messages. The Zoo intended to reach as many visitors as possible. Another role of the graphics is to encourage observation by the visitor. Taking advantage of the under-water view, it is pointed out that these hippos do not move by swimming but must walk or run on a river bed. This is the interpretive element which aims to allow visitors to make sense of what they see and confirm what they read for themselves as well as simply enjoying the grace and agility of the hippos seen this way.

Habitat is addressed factually without much description or pictures. Therefore it is important that visitors correctly interpret what they see. Visual accuracy is thus more important than in older style exhibits where no apology was made for lack of habitat representation. Even naturalistic displays will not be understood as real habitats. It is an article of faith that habitat simulation will be interpreted by visitors as such. Therefore compromises, if not explicitly addressed will give rise to misconceptions. Even if a feature is correct, it may be misinterpreted, as by, for example, those who thought hippos eat fish in a display where fish share the same pool. Beside the obvious idea suggested by the exhibit and confirmed by the graphics that hippos come from an aquatic environment, an equally large number said ‘riverside’, and one even said ‘jungle’, after seeing the exhibit, which are also aspects of the hippos’ natural environment.

The other significant perception concerns the perennial zoo issue of confinement and lack of freedom. The exhibit space is backed by a simulated ‘mud bank’ retaining wall higher than necessary for restraint. This space curves away out of view where a passage exists to the night quarters. It is still a well-defined space. The land area is large enough for such an aquatic animal, and visitors probably do not have much argument with this. From comments made, visitors feel that the hippos have too little space because the animals spend most of their time right by the glass. They feel the animals are forced into this situation, which in a sense they are, though not physically.

The pool is shaped with broad shallows dropping to a depth of about a metre along the glass front. The depths reflect the two main uses of the pool for the hippos--moving and reclining. The hippos do, in fact, use the whole of their exhibit space but do also spend a large amount of time in the deeper water bounding up and down the pool length. Visitors are not concerned at the amount of time spent in this way, but that the space in which the hippos perform this activity appears too small. This is due largely to the water and air interface that enlarges object and foreshortens distances.

the issue is not the actual area given to these terrestrial/aquatic hippos; it is the perception of it. Several things might be done in response to these concerns. Among them would be the following:

- to address the issue of behaviour in educational graphics;

- to discuss the needs of the animals more specifically in contact sessions with keepers;

- to modify or re-landscape the pool and land area.

Figure 84 Pygmy hippo viewing gallery

The latter could only work by introducing some ambiguity or areas hidden from view as the physical dimensions are fixed. other forms for display pools exist which avoid this perceived defect such as including a central shallow area in addition to the periphery [2]. All involve the possibility of the hippos spending some of the considerable time they spend moving about away from the viewer or even obscured. This may work better with the larger and more social Nile hippos. It should be pointed out too that the need to cleanse the pool does not disappear with habitat design and this has a considerable influence on pool shape.

Finally, it is probably safe to say that visitors mentally separate the artificiality of their environment from that of the animals; but whether the realism of the view is sufficient to give the illusion of habitat, and of the animals being in the wild, without resort to landscape immersion is an open question. This study reveals both that visitors feel the animals are still too obviously confined and that they draw conclusions about the way of life of hippos from the exhibit itself without the aid of graphics.