The Role of Architectural Design in Promoting the Social Objectives of Zoos

A Study of Zoo Exhibit Design with Reference to Selected Exhibits in Singapore Zoological Gardens

by Michael Graetz

PART 2 - PHYSICAL ELEMENTS OF ZOO DESIGN

2.4 Exhibitry: The Tools of Habitat Simulation

The technologies available to exhibit designers have spawned a whole industry dedicated to exhibit construction. Such firms may be employed to build whole exhibits or to ‘dress’ the shells of enclosures built by more conventional means. Once the realm of keepers and gardeners, this aspect of finish often referred to as exhibitry is now the subject of a debate over the purpose of realistic habitat portrayal.

The term ‘exhibitry’ encompasses and goes beyond the older term, ‘exhibit furniture’. Both may refer to the dressing of the bare enclosure. Furnishing suggests a functional approach and traditionally is often left to zoo staff with keepers ensuring the basic needs of animals are met and horticulturists looking after the aesthetic elements. Exhibitry implies a role for an outside specialist which in practice is usually a combination of a designer and a specialist fabricator, but other permutations are also found, such as contractors working with in-zoo designers. Generally, however, there is a shift in control over new exhibits away from the zoo and its operational staff which alarms many in the zoo world [1]. Exhibitry sounds to some like gimmickry. Such concerns are justified if exhibitry becomes the end rather than the means. It is well to know what is being simulated and why, and appropriate materials and techniques chosen accordingly.

That controversy aside—or perhaps to allay it—the designer needs to understand the reasons for the features expected by the zoologist or curator, and the sensory elements for the visitor. Planning for an exhibit should involve some degree of research into the appropriate habitat features. Thus informed, ingenuity, studied carelessness, whimsy and an eye for nature are to be cultivated. Willingness to adapt to circumstances as the work progresses is also often as important as the careful planning that should precede it.

Fig. 30 Viewing bay at the duiker (Cephalophus spp.) exhibit

Recreating Habitats

The ‘Gaia hypothesis’ proposed by James Lovelock[2] holds that the whole biological-physical system of the earth can be regarded as a single entity, self-adjusting just like a living organism. Viewed against this, the best of man-made conditions in zoo enclosures may be considered woefully inadequate as self contained environments and the title of this section is a contradiction. This does not mean there is no point in attempting to replicate natural conditions: animals are remarkably adaptable and a naturalistic environment will not necessarily be indistinguishable from an unnatural one.

Some of the natural sub-systems which are important in habitat simulation are as follows, followed by comments on their relevance:

- Geology and geographic features

- Climate

- Botanical character

- Ecological relationships

- Habitat and habitat niche

The effect of the underlying geology on the vegetation of an animal's habitat through the agency of soil has been referred to in an earlier chapter. It may also determine the local soil colours and textures, mould the topography, appear as surface features and, if dominant in the landscape, be significant for animals—for shelter, escape, climbing, etc.

The natural history of such rock is also relevant to achieving the correct appearance. Rock may be igneous, sedimentary, etc. in origin, and its present character determines its history since formation. This is a combination of colour, texture, grain and angle of the grain, size variation, how it fractures, weathering, form (shape). A zoo rockscape, whether from natural or artificial stone, should recognise these characteristics and, for example, maintain the slope of any grain. The extreme range of particle size in eroded or weathered formations is also often disregarded. Rocks may range from monolithic structures, to boulders and to pebbles within the same formation.

Climate is a highly variable factor arising from the planetary motion of the earth and solar radiation, which set up winds and ocean currents. While climates derive from these interactions, the microclimate at any given location is the result of many systems. The localised climate may be erratic or stable, relatively uniform or exhibiting a wide range of variation over different time-scales. Zoos in temperate regions find it difficult to moderate conditions for tropical animals. Humid-tropical zoos such as Singapore have problems mostly with arid land creatures. Microclimates even within the area of a zoo can be significant and influence the siting of exhibits [3].

‘Habitat’ is the locality or environment in which the animal lives. A biome is the totality of plants and animals that share and make up a particular habitat type over the entire geographical area with the same habitat; whereas an ecosystem is any relatively self contained system of plants and animals. Ecological relationships can usually only be simulated in zoos. Even when so-related species are kept physically together, this is just one strand in a very complex web, which can be used interpretively.

The niche comes down to the level of a species and is a subset of the habitat, so to speak. It is not simply the physical place, such as tree tops or rock crevices, occupied by the animal, but also its role—or place—in the ecosystem, such as different species of vultures, which feed on the same carcass at different stages of disintegration . Often, zoo ‘habitat exhibits’ are actually seeking to represent animal niches, which due to their natural variability in many cases, actually give the designer and the zoo a great deal of scope to adapt to circumstances and create a sense of a particular place, rather than a generic habitat scene.

Fig. 31 Old moat edge treatment at Barbary sheep (Ammotragus lervia) exhibit

Techniques for Habitat Simulation

Artificial rock and earth. When exhibitry is presented as a package, it is usually based around the artificial geological formation, encompassing the barriers and/or their concealment. The means of capturing real rock and earth character artificially are available but expensive. Many zoos feel this cost is unjustified. This may be valid in terms of choice of materials but as the difference between good and bad work is in the craftsmanship, artificial rock in zoos is often of a type found nowhere else, a generic zoo rock. There are stylistic differences, of course, but they share the common characteristic of failing to look real.

There is also the question of whether rock at all belongs in the exhibit. Polakowski sums up the debate over how accurately ‘habitat’ needs to be portrayed, thus:

. . . some designers believe that . . . in many instances a setting with simulated rock outcroppings is inappropriate to the animal's native habitat. . . . Many exhibits representing this design approach are unsuccessful because the essence of the native habitat was never realised and/or the physical abstraction of the essence was poorly conceived and executed. The lack of sufficient space for animal exhibits on the zoo grounds has helped perpetuate the need to abstract, in size and atmosphere, the natural habitat. [4]

In the face of such difficulties, even the use of GFRC and Gunite can become the easy option which avoids the need to think about each new exhibit afresh. Shunning extravagance should not be a justification for expedience.

In creating artificial rock formations, two principles can be confused: consistency (e. g. of grain, texture) and variation (e. g. of colour, scale). Thus, relatively uniformly sized boulders arranged with no regard to the original bedding planes may be the result. In designing such rockwork, sound construction can be specified but there is no sure way of unambiguously detailing or specifying these qualities. The best approach is to engage fabricators with known track records, be prepared to use additional means of communicating the desired character (photographs, samples), and develop a critical eye for assessing the result.

Fig. 32 Damage to GFRC rock by elephant (‘Night Safari’)

Other artificial materials. Virtually any natural object is nowadays simulated in epoxy resin or other compounds. Common items such as corals, an barnacles for aquaria are effectively a mail-order business. Artifacts which would not normally be considered, such as fossils, are just as readily supplied and if not, will often be made to order. Vines and lianas are ordered by the metre, graded for suitability for different primates. Trees come with very realistic lichens painted on (a necessity in polluted cities). The bark can be made in varying grades of realism depending on how close the visitor is able to view it.

Fig. 33 Framed view of Greater Kudu (Tragelaphus strepsiceros) exhibit

Although this dissertation is concerned primarily with outdoor exhibits in a tropical zoo where such effects can be achieved naturally, the durability of such products as well as their educational possibilities make them worth considering, provided proper thought is given. Brady et al after describing the elaborate simulation techniques used in Cincinnati Zoo’s ‘Cat Exhibit’ for eighteen species, emphasise that these were used for a purpose, not simply for effect, and required considerable effort:

Habitat research played a major role in the design of

the Cat Exhibit because of the desire to represent, with scientific

accuracy, the natural environment of each species. . . .

The new design . . . serves the parallel functions of providing and environment mindful of the health, well-being and breeding of the wild cat collection while also educating visitors. These goals were met through the careful research and expense, both in labour and finance, . . . . painstaking attention to detail throughout the building and the effort to link the natural history of wild cats to the human experience . . . [5]

Natural materials. These largely depend on what is available in the locality or region of the zoo. At a time when habitat can be simulated with totally artificial materials, there is as strong a need to use natural materials as in the ‘bathroom’ phase.

As Poole says:

It is important to be aware that some ‘naturalistic’ displays are totally artificial and consist of concrete rocks and plastic trees and foliage. While these may deceive the public, primates and many other species will, in most cases, be aware of the artificiality of the setting. Such displays are stage sets which only provide an illusion of nature and at the best simply provided a climbing frame for the inmates. [6]

Natural stone should by all means be used but not overdone unless the zoo is fortunate enough to exist in a geologically rich area, or all exhibits will begin to look the same. Stone can be imported, but this is limited and expensive. It is doubtful that a realistic rocky landscape can be created with this. These are two arguments for artificial rock..

Fig. 34 Gunite riverbank in the duiker (Cephalophus spp.) exhibit

One use of natural rock, if compatible, is to lend realism to artificial rock, but mostly it will be used sparingly and on its own. Mature trees, live and dead, are an important resource for zoos. Jackson discusses techniques for maintaining tropical simulations in a sub-tropical zoo which is a lesson in ingenuity and opportunism—old, overgrown plants discarded by nurseries, fallen trees overgrown with creepers, for example [7].

Dead trees are often obtained opportunistically when they fall or die naturally or are felled by developers in the locality. Besides their obvious use as climbing structures, they have some advantages over artificial trees. Among these are the following: they provide therapy to animals which eat or peel the bark, or hunt for creatures living in the decaying wood; they support epiphytes; and demonstrate natural processes not seen in manicured parks. Natural branches also provide a dynamic element for brachiating and climbing animals through their springiness, although this can be simulated.

Fig. 30 Viewing bay at the duiker (Cephalophus spp.) exhibit

Trees are useful right down to their twigs. Brush may provide a sense of security for some animal and perches for many birds. Scherpner told this author that a species of small antelope in Frankfurt Zoo had experienced eye problems in their winter quarters until some brushwood was introduced. It was observed that the animals began scent marking the points of twigs from glands near their eyes. Without this habitat feature, they were unable to perform a vital behaviour [8].

Fig. 36 Non-random pebbles on a beach

Substrates

‘Substrate’ is a zoo term generally applied to the surfaces animals come into contact with in zoo enclosures. The idea is a zoo-biological one, but the idea of surfaces is also a very architectural one. The idea is extended here to include the tactile and visual experience of visitor paths and spaces.

Landscape immersion implies the same substrates are used on the public side of barriers. Some concessions have to be made for human ergonomics and comfort and as with the need for functional planting schemes for both sides of the barriers, some skill and ingenuity is required to achieve a unified visual appearance. Very often the visual-tactile appearance of the exhibit substrates belie the perfection of the visitor’s environment. One approach is to treat the hardscapes on the visitors side as geological or geographic features similar to those used in the exhibit. To this end, practical path constructions and widths, gradients, etc. for the traffic load are necessary and yet must be plausible elements of a natural landscape—not a sidewalk.

Fig. 37 Variations in paving textures—formal and informal

Paths. several variables can be manipulated in this, the primary tactile element of zoos for visitors:

- Width. Paths should conform to the topography, but variations in width combined with bends keep them from being predictable. Exposure to vistas and views can be delayed, or shown from a distance; choices at junctions can to some extent be controlled.

- Finish. Gunite, salt finishes and pebble finishes have been used with earthy colours, variations in textures (without being hazardous) and random, accidental notes such as larger pebbles, leaf impressions, even animal tracks.

- Edge treatments. These can extend the mud bank theme of the habitat, for example. Again objects can be embedded—tree roots, stones, bones. Perhaps the simplest edge treatment is to allow adjacent vegetation to overgrow the edges. If the traffic is intense enough, it will be self-trimming.

Fig. 38 Natural path edge treatment that also allows for child views

‘Street furniture’ is a human requirement; and although the same mud bank retaining a planter may serve as a seat, benches, along with rubbish bins, drinking fountains, directional signs and graphics are essential features. As noted elsewhere, much of this can be associated with shelters or comfort stops between exhibits.

Fig. 39 Example of a boardwalk (walk-through snakes)

Behavioural Enrichment

Firstly, if behavioural engineering, the alternate term, means controlling animal behaviour, then the primary use in Singapore Zoo involves the ability to keep many animal species in open enclosures with ‘barriers’ which are within their physical capabilities to cross, i. e. psychological restraint. The experience of Singapore Zoo with this technique is discussed fully by Harrison [9].

Fig. 40 Boardwalk with ‘guest’

Behavioural enrichment, as it pertains to built elements of simulated habitats is perhaps exhibitry with a conscience, or a concern for animals. Never-the-less, enrichment has benefits for visitors. It is aimed at improving the lives of wild animals in captivity, with the secondary objective of improving the display. Some controversy surrounds the field, however, on the question of what methods are best and whether the behaviours stimulated are indeed natural [10]. This controversy will not be entered here, but the term ‘enrichment’ is used in preference to the alternative of ‘engineering’ [11] as the electro-mechanical random feeders typical of the latter are difficult to design and install. They are much talked about but in little general use.

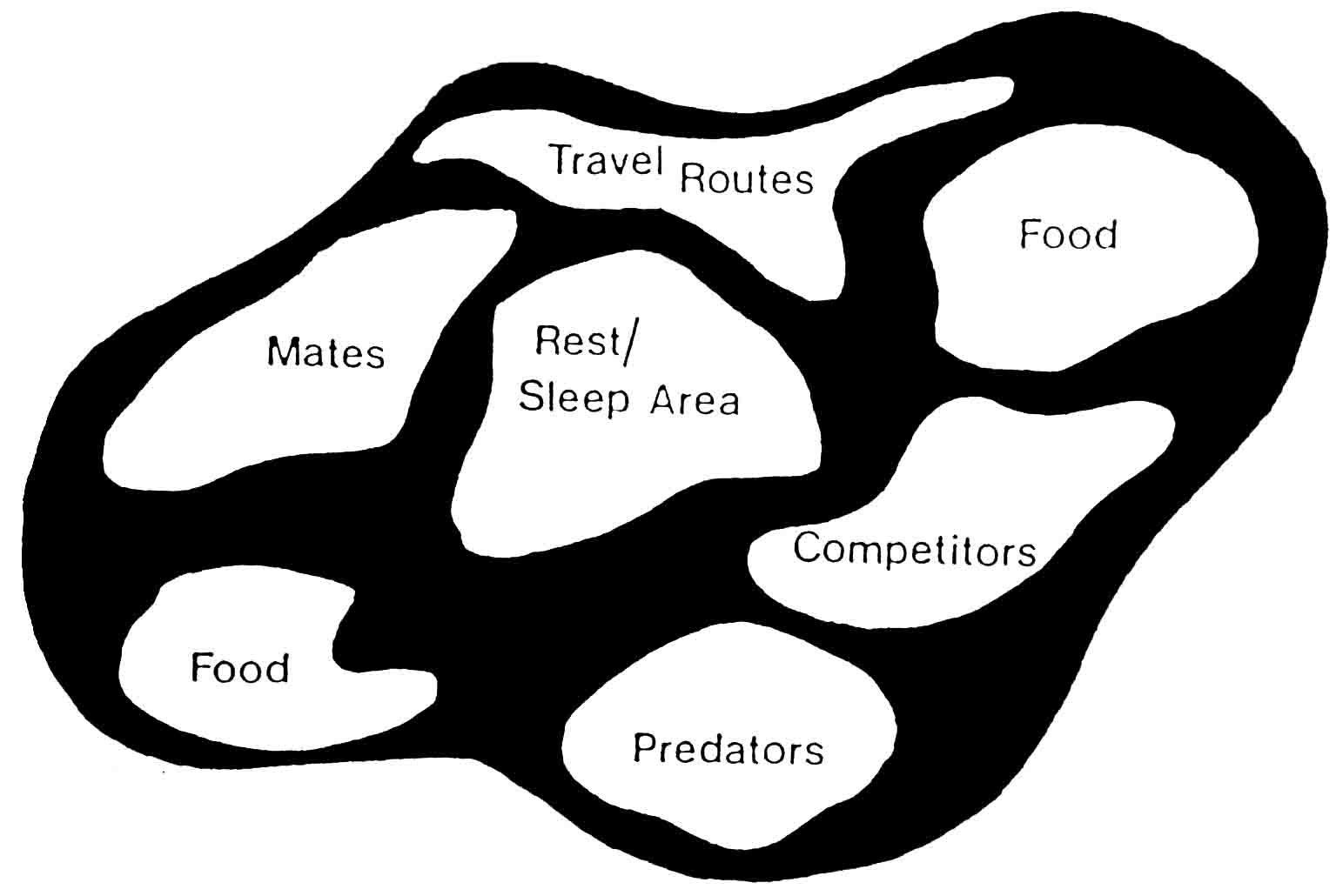

Fig. 41 The psychological space (home range) of animals—physical and temporal; from Sheperdson

Much of the naturalistic school of thought is in fact referred to throughout this dissertation incidentally. Since it is intended to stimulate animals to display their natural repertoire of behaviours through exhibit modifications, ‘environmental enrichment’ may demonstrate the link with architecture. For the designer, the first need is to create the right facilities in which this can take place. Ease of access for introducing new objects and of movement of keepers to ‘plant’ forage items should be considered.

Secondly, although keeper management is important, the objective of the designer should be to create as rich an environment for the animals as possible. Low cost use of natural materials and generally keeping the animals’ environment as complex and variable as possible. This includes making it possible for keepers to make changes.

Fig. 42 Sun bear (Helarctos malayanus) pit with ‘honey tree’

Thirdly, some less technical devices such as artificial termite mounds are fairly common and worthwhile. These dispense honey, condensed milk, various forms of gruel either extracted by poking sticks into holes as with chimpanzees; or made to slowly flow out for bears and orang utans, to name two examples from Singapore Zoo.

Whether such devices are necessary to compensate for the inherent deficiencies of captivity, or whether enclosures with the necessary features for the full behavioural expression can be designed without them is debatable; however, it is important that the solutions are suggested by the basic concern entering the design process:

The zoo designer should have two main aims. Firstly to ensure that the needs of the particular species are met in the enclosure and, secondly, to present the animals to public view in an effective manner. Thus the zoo designer must be concerned about the animals' behavioural needs because he wishes the public to observe the animal behaving in as natural a manner as possible. . . . Good zoo design and animal welfare are inseparable. [12]

Fig. 43 Orang utan (Pongo pygmaeus) island with climbing frame, hammock and nest material, and condensed milk dispenser

Authors such as Shepherdson [13], Anderson [14] and O'Grady et al [15] represent a range of views on the elaborateness of these devices. Shepherdson describes a number of devices for caged animals, such as a very simple mealworm dispenser. Anderson’s devices are more elaborate but mechanically quite simple also. They are mainly intended to enliven the indoor quarters of chimpanzees. They have to be regularly renewed and are supplemented by natural materials. Markowitz makes extensive use of electronics to overcome the predictability of the simple devices.

Fig. 44 Moat edge and ‘hot’-wired tree in the Lion-tailed macaque (Macaca silenus) island

There are two principles behind the success of these devices. Firstly, behaviour is stimulated by the prospect of a reward. The reward is a token one and not easily won and the outcome of the behaviour (to get a reward or not) is not certain. Secondly, some effort and use of intelligence is required of the animal. Very often animals devise a strategy to get the reward with less effort than the behavioural engineer anticipated and lapse into the same inactivity. This was experienced in Singapore Zoo’s chimpanzee ‘termite mound’. Instead of using grass stalks intended as a substitute for sticks, the chimpanzees chewed the stems into brushes to clean out the condensed milk contained inside. [16]

The development of similar feeders for other species required a number of prototypes to perfect the rate of dispensing (by gravity) and ease of collecting by the animal. In all cases, they require an informed guess at the first prototype followed by cycles of observation and modifications. For this reason devices in Singapore Zoo are extremely simple. The honey tree described by Anderson involves a honey pump operating randomly [17]. The Singapore version involves an inverted, punctured condensed milk tin placed by a keeper at intervals.

Discussion

Exhibitry in zoos is influenced by techniques developed from two diverse sources. One is museums and the other is theme parks. The case for museum techniques is natural; though dealing with (largely) inanimate exhibits, this has lead to a great deal of expertise and skill in recreating replicas of natural environments and life-like models of animals and artifacts in museums of natural history. Science museums have contributed much to interactive devices which allow visitors to do more than passively view exhibits. This makes for a more memorable experience. All forms of museums of course are innovators in graphics.

The theme park is an outgrowth of amusement parks combined with the spectacles of thematic displays. The idea was fully exploited by Disney in the 1950s, while the great World's Fairs which were held from the nineteenth century featured large scale dioramas. Some of these were produced by Hagenbeck, which obviously directly influenced his own ideas about zoo design.

The drawing of zoo exhibitry techniques on these two trends, theme parks and dioramas, is reflected in the debate on the validity applying a veneer of reality to something obviously artificial. Some say zoos must employ such methods to compete with Disneyland. Others say these methods are a means to an educational and interpretive end, and that education has to be made interesting, if not entertaining, rather than boring. Yet still others argue, as Poole does [18], that the realities of animals' lives in zoos is also something visitors need to be told about.

The borrowing of techniques from such diverse sources can lead to confusion and distrust about the aims of exhibit design. The philosophical viewpoint of redressing the balance in favour of animals has to be kept in view. Coe describes it as a shift from a homo-centric view of the world to a bio-centric one. He paints word pictures of the alternate views thus:

A bear splashes in a bathtub sized pool in a large grotto of carved concrete. The implicit message might be that Bruin and his kind live a benign existence in arid box canyons. . . . The true facts of this major predator's existence may be explicated on adjacent sign boards but the information is overwhelmed by the stronger contrary message of the hard barren exhibit. [19]

This he compares with:

. . . an exhibit in which visitors follow narrow paths between willow thickets and rough boulders towards the sound of falling water. Through a small clearing they see a powerful cascade and, chest deep in a torrent, a grizzly fishes for dinner. There is no visible separating moat or other sign of obvious containment. The grizzly ignores us because he has better things to do. . . . The message is no longer one of comfortable, complacent domination, but one tinged with awe, grandeur and, perhaps, humility. The effectiveness of the communication is measured with the pulse rate of the visitor! [20]

Each zoo and its design team ought to be aware of the messages they intend to convey and not aim to entertain for its own sake. As with all architecture, the solution reflects the intention and the problem as it is defined. The exhibitry materials and techniques used should be chosen and applied with this in mind, rather than to follow a fashion. The resulting exhibit should be able to answer critics of the impact on both the visitors and the animals.