The Role of Architectural Design in Promoting the Social Objectives of Zoos

A Study of Zoo Exhibit Design with Reference to Selected Exhibits in Singapore Zoological Gardens

by Michael Graetz

PART 2 - PHYSICAL ELEMENTS OF ZOO DESIGN

2.5 Designing in Graphics

Graphics in zoos have evolved dramatically from simple scientific name labels to “seemingly endless paragraphs silk screened on endless walls, . .” [1], to simpler messages with lots of pictures. Serrell defines educational graphics as, “both signs with text and signs with text plus art” [2]. A broader definition includes not only signs but also models, artifacts, electronic (audio and visual) media and interactive devices; however, similar principles of designing the graphics into and with exhibits apply.

Singapore Zoo commissioned a signage master plan from Charles Beier, a graphics specialist from the Bronx Zoo, that has the objective of rationalising the multiplicity of graphic styles and materials accumulated over its short history. Achieving this with all the free standing directional informational and educational signs is conceptually easy. The difficulty lies in writing off the sizeable investment in the existing stock of signage. It takes time. Further difficulties are encountered in gaining consistency in graphics and signing inside display buildings because each building is usually unique in its design.

With a master plan, achieving consistency through a wide variety of needs is also difficult, even in considering only exhibit graphics. The needs include educational graphics, standard labels, announcements of births or new arrivals, donor signs and warnings (‘danger’, ‘no feeding’ etc.). A variety of typical signs in Singapore Zoo are illustrated in this chapter. Within often small exhibit frontages the different styles can jar, and similar signs still must be co-ordinated and positioned carefully. The remainder of this chapter considers some theoretical issues relating to the content of exhibit graphics and how they should relate to overall exhibit design.

Fig. Standard aluminium animal legend

The information content of exhibit graphics will have one of two basic characteristics: either it explains the apparent features of the animal and habitat, or it offers additional information not available in the exhibit proper. Which of these principle roles are chosen for exhibit graphics thus has an impact on the design of the exhibit. This chapter discusses these implications and some possible ways graphics can be integrated with exhibits.

The role of graphics. Educational graphics is an accepted requirement for exhibits. We could argue, however, that visitors will understand the ideal habitat simulation exhibit without need of graphics, and that signage destroys the illusion of habitat immersion. At best, we might consider graphics a necessary compromise, at worst, a sign of failure. The converse might also be thought true: that with excellent graphics, good habitat simulation is unnecessary. Both attitudes are too extreme and need rebuttal.

Fig. 46 Temporary sign for new arrival (bontebok)

First, exhibits do not fail because they require graphics. For various reasons we cannot expect that visitors come armed with the necessary or sufficient knowledge to understand the animal or its habitat, and so they need explicit information. Second, the signs themselves can be compatible with immersion landscaping if both are treated as educational elements. The idea that they are not compatible assumes that landscape immersion is the end in itself rather than the means.

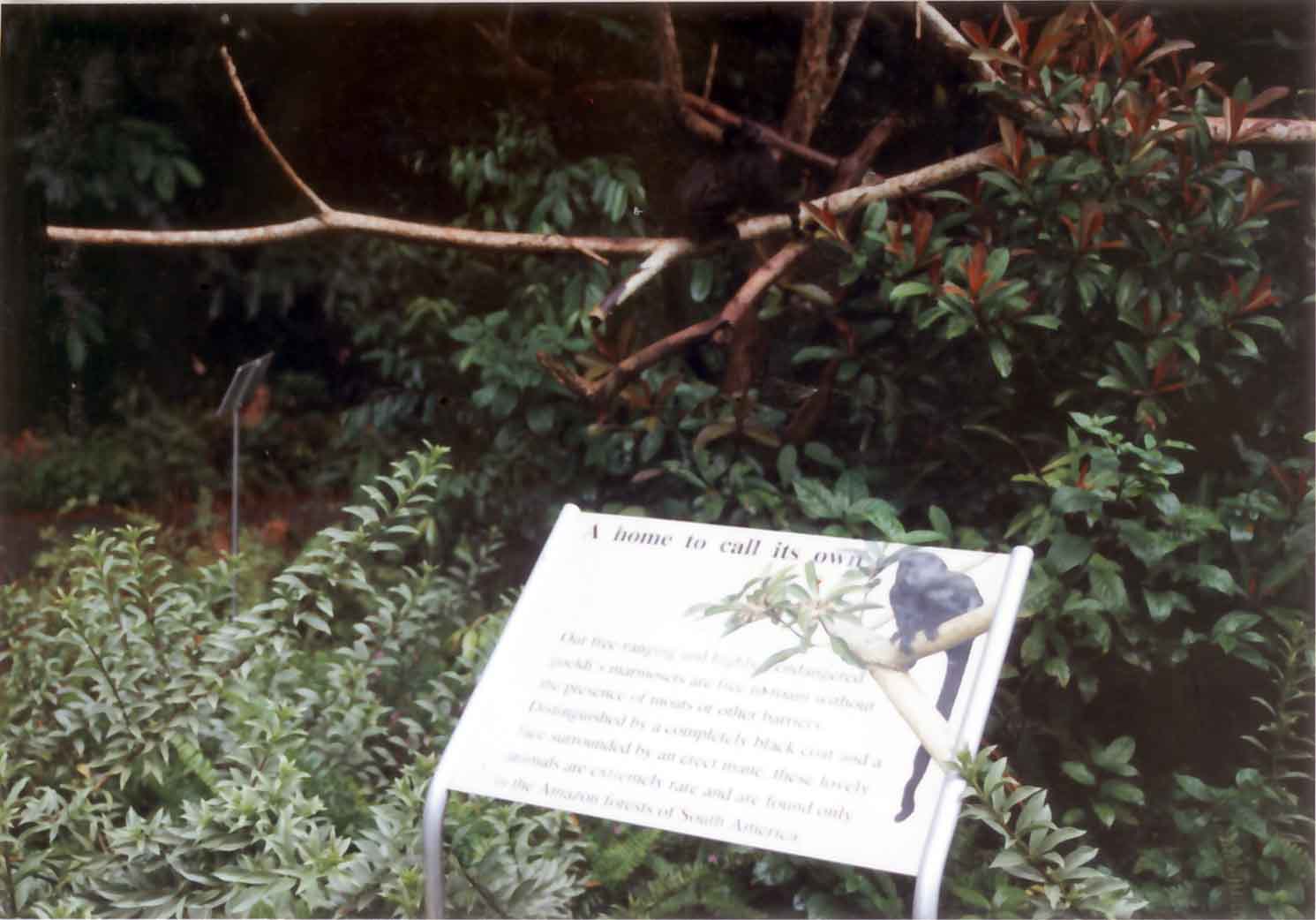

Fig. 47 Two signs for free ranging Geoldi‘s marmoset

immersing visitors in a simulated habitat is only one way of showing animals for what they are and on their terms. This is especially so when we hope to inspire the desire in visitors to see that the animals and their habitats survive. With immersion landscaping plus graphics, the illusion should be strong enough to achieve the purpose.

Lastly, poor quality animal exhibits will detract from the message of good graphics. The more opportunity given by the animal display for things to talk about, the greater will be the impact on the visitor. Additional information is good, but will lack the immediacy of having its reality before the visitor's eyes.

With so-called ‘good’ exhibits, difficulties can exist too. Trevor Poole points out that animals in immersion exhibits with behavioural enrichment programmes have reduced visibility in complex settings and may give a false view of normal activity budgets. Thus:

For good zoo exhibits therefore it is essential that there is information which tells the public what they may or may not expect to see and some comparison between the facilities provided and those available in nature. If the animals are invisible the viewer should be encouraged to be patient and read information provided so that the chance of seeing the animal is increased. [3]

The problem of visually and experientially ‘good’ exhibits giving misleading impressions is inevitable since most visitors will only see an exhibit for a matter of minutes only. It can only be overcome through some form of interpretation.

Fig. 48 A botanical sign on etched aluminium

Interpretation versus information. The two types of graphics referred to at the beginning of this chapter are called here interpretive and informational [4]. The distinction is important because the first works only if the exhibit portrays the chosen themes. Most authors view this mutual support between exhibit and graphics as more effective than simply providing extra information. Anderson maintains that it is not easy, however. Ideas like “endangered” are too abstract for interpretation:

It is not immediately understood by a zoo visitor that the white rhinoceros, the gorilla and the gaur are endangered, and . . . it is difficult to help the visitor to realise this through their own experiences. An endangered species in a zoo looks like all other zoo animals - it does not look at all endangered. [5]

Within the definition of interpretation two models exist that, according to Anderson [6], also have design implications. One tries to provide answers to questions visitors ask themselves; the second tries to suggest aspects to visitors that they can verify by observation. In the first, exhibits must be designed to prompt the questions, which is more difficult. The second challenges preconceived notions and encourages observation. Milan and Wourms recommend a mixture of both[7]; while d'Agostino et al suggest that the problem of changing visitors' attitudes is also difficult and controversial [8]. Hatley calls this ‘hot interpretation’ in which visitors are moved, “through shock to anger”, rather than made to feel good. For this, “there must be no conflict between the medium and the message” [9].

Conceiving Exhibits in Graphic Terms

An obvious consequence of the need for graphics compatible with the exhibit is that the two should be conceived together. This is not simply a matter of ensuring space or means of installing the graphics. Designers speak of exhibits that tell a story, which mean exhibits that convey a message. Exhibits must fulfil the needs of several user groups and it is easy for any one of these to have too much influence on the design. The conscious message may be clouded by the unconscious expression of keeper, or maintenance needs, for example.

Fig. 49 Temporary directional signs for new exhibits

Increasingly more elaborate conceptions might consider an exhibit as: an artificial habitat tailored to the animal to the best of our scientific knowledge; a diorama or tableau, a snap shot of the animal in the wild; a theatre complete with proscenium and props for the behavioural performance of animals; or a landscape which visitors actively participate in, encountering animals—often prey and predator ‘together’—as they move through a thematic sequence.

Grouping exhibits according to taxonomy or geography or biomes are only the most obvious themes. Other possibilities include: habitat grades—littoral to montane; parallel evolution—similar morphological adaptations among widely separated species; or cultural or ethnographic themes—the process of domestication, conflict between indigenous peoples and dwindling habitats. Many of these can be overlaid to present several storylines at once. Such approaches will not be possible without the interpretive, which is to say, graphic issues in mind from the outset.

Fig. 50 A ‘You are here’ sign—stainless steel is a practical consideration for Singapore's climate.

See also Figure 109 for an example of a finger directional signage system

Most authors agree on basic principles of exhibit graphics. Sanford and Finlay identify attractiveness and ‘communication performance’ as factors in the effectiveness of signage. They list three characteristics of signs: 1) informational content; 2) graphic presentation; and 3) sign location. Thus, signs should be intrinsically attractive, placed within the movement patterns of visitors and there should not be too many.[10] Serrell and Anderson, two authors already referred to, add that signs should be in line with the exhibit so that visitors can easily verify the content by looking up.

Another point frequently made is the dictum for the designer to know the visitors. Bitgood et al lists the relevant visitor characteristics as demographics, special interests, tiredness, perception of the animal, and behaviour in the zoo [11].

Serrell, on the other hand, says:

Social and psychographic characteristics of interest and motivations for visiting have more direct implications for zoo graphics than do demographic characteristics such as age groups, income levels, and zip codes. [12]

Milan and Wourms and Serrell both emphasise an understanding of what motivates people to visit zoos with the latter suggesting that zoo goers do not score as high in knowledge tests as other special interest animal groups. Schibley, however, suggests that visitors have sophisticated perceptual abilities due to the influence of films and television [13]. It is probably more likely though, especially in Singapore, that people's sensory sophistication is a product of their own urban environments more than those seen on the screen—or in the zoo. Serrell states that visitors will react emotionally (rather than intellectually) to experiences with animals, since they lack the knowledge and experience zoo personnel have.

A major concern of zoos is how much visitors learn both for their own benefit and for the promotion of attitudes zoos would like to further, I. e. conservation education. Zoos provide both a venue for learning through programmes conducted by zoos and others such as teachers, and are in physical environments in which people learn passively, or informally [14]. Organised programmes may impinge on the architecture when a brief calls for specific spaces or facilities for these, but this dissertation is concerned with the role of exhibit design.

The most important element in the educational content of an exhibits is, of course, graphics. The point is made that exhibit and graphics should not contradict each other; and interpretation, meaning to help visitors understand their experience of the exhibit, requires the graphic messages to be decided and linked to the exhibit in some way. The evidence now strongly suggests that, as Coe says, the inherent meaning in the exhibit often contradicts the overt message the zoo intended to convey.[15] Zoos are urged to go beyond merely naturalistic exhibits.

Fig. 51 Timber sign announcing animal feeding, an educational programme. This style is used for major exhibit markers

Exhibit design is thus concerned with how to ensure the messages are read and how much is understood. In this, placement and design of graphics are important, but the exhibit designer must be equally concerned to encourage direct observation. This author has observed school children armed with worksheets laboriously copying down details of animals from the legend in front of the exhibit and even tracing the silhouette of the animal, while hardly glancing at the living animals before them.

There is obviously only so much an architect can do before it becomes a matter for docents, demonstrations, feeding and other activities. The task is quite onerous, in fact, when it is considered that the graphics must be placed in such a way that they will catch visitors' attention; the exhibit must do likewise; and the two must be juxtaposed in such a way that visitors can see the two together—or the educational opportunity may be lost. What is doubtful (and it is an area in need of study) is whether visitors do read a fact and look up to confirm it; or whether they notice something about the animal and check the graphics for an explanation.

Fig. 52 Donor acknowledgement plaques in stainless steel

Churchman and Hanson, however, give three reasons for using architectural devices to guide visitors purposefully: the nature of science, which is complex and abstract; the nature of memory, which is aided by placing information in a context; and the nature of perception, “which moves from the concrete to the abstract”. [16] Naturalistic enclosures which portray habitat are also said to require less text. One point which is important to remember is that visitors, especially the typical family unit, are willing participants in this informal educational process. They are, however, subject to fatigue, boredom, inattention, distractions, hunger, thirst and so on, so that the goal ought to be to create as conducive environment as possible within an exhibit and throughout the zoo.