The Role of Architectural Design in Promoting the Social Objectives of Zoos

A Study of Zoo Exhibit Design with Reference to Selected Exhibits in Singapore Zoological Gardens

by Michael Graetz

PART 4 CASE STUDIES

4.5 Primate Kingdom Case Study

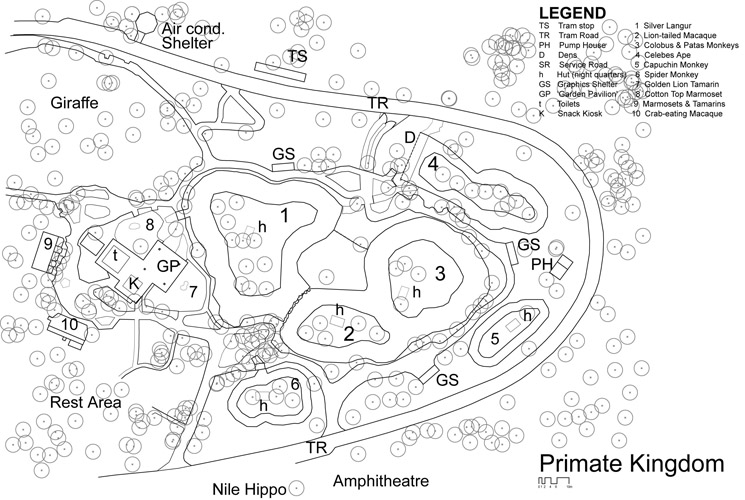

Primate Kingdom is a group of exhibits which were planned to break with the previous convention of small primate islands in Singapore Zoo, and also to introduce landscape immersion into a totally new development as opposed to the previous introduction of limited elements of this into upgraded exhibits.

Being small to medium sized animals generally (except for the great apes), primates were formerly regarded as being bad subjects for large exhibits. They would be ‘lost’ in a big expanse. And while live and dead trees were always standard exhibit furniture, exhibits were uncluttered to ensure good visibility of the animals. The new grouping on the other hand was planned to consist of large islands and be thickly wooded. The result should be regarded as habitat simulation rather than full replication; and this simulation extends to the visitor areas through landscape immersion. Table VI gives the species displayed on the five islands, their geographical representation and the areas of the islands.

In comparison, all older monkey and lemur islands were made much smaller: Muelleri gibbon, Hylobates moloch muelleri--169 sq. m.; white-handed gibbon, Hylobates agilis--129 sq. m.; spider monkey, Ateles paniscus--144 sq. m.; and three generic lemur islands--75 sq. m., 67 sq. m. and 100 sq. m; all elsewhere in the zoo. Notably, all species in ‘Primate Kingdom’ have bred and are casually observed not to show obvious signs of stress from being on public display.

Figure 90 Plan of ‘Primate Kingdom’

In addition, there have been three other phases of development of primate exhibits in this area; two earlier ones and one more recent development. The Celebes black macaque, or ape as it is also known, was an original moated display--not an island--which was doubled in size and turned into an island with the ‘Primate Kingdom’ development. Also original were a group of three identical cages for primates. One of these was converted in 1984 into a breeding area for marmosets and tamarins with a series of side-by-side glass fronted display cages. Of the remaining two cages, one was demolished in the latest phase and the other was used to display de Brazza monkeys, pending demolition as well.

Table IV PRIMATE KINGDOM: SPECIES AND EXHIBIT AREAS

SPECIES |

ISLAND |

AREA |

|---|---|---|

(sq. m.) |

||

Brown lemur, Lemur fulvus |

Island 1 (Madagascar) |

219 |

Lion-tailed macaque, Macaca silenus |

Island 2 (South India) |

300 |

Capuchin monkey, Cebus apella |

Island 3 (South America) |

153 |

Colobus monkey, Colobus guereza |

Island 4 (East Africa) |

460 |

Celebes black macaque, Macaca nigra |

Island 5 (Sulawesi) |

303 |

Silver langur, Presbytis cristatus |

Island 6 (South East Asia) |

706 |

TOTAL |

2,141 |

The recent development has been the introduction in ‘Primate Kingdom’, and in several other areas of the zoo as well, of ‘free ranging’ marmoset exhibits. Since it was pioneered in Apenheul in Holland, this technique has been tried and refined to the point where these smallest of monkeys can be encouraged to set up territories in quite small areas in view of the public, without straying. This is an advance on Apenheul's innovation, since climate and vegetation in the European setting help to retain the animals in their designated area near food and shelter. The Singapore application demonstrates that territoriality is a powerful motivation to stay put. Since it is pertinent to this case study, the siting of this development within the zoo should be mentioned. Three factors went into the choice as follows:

- The area on the northern lobe of the zoo had relatively few existing exhibits and was consequently seen less by visitors.

- There were already several old, small primate exhibits in the area which could either be displaced or incorporated in the new scheme. Other existing features, such as ornamental ponds, could easily be displaced.

- The site was large enough to permit expansive island enclosures with wide water moats and at the same time allow visitors to be fully immersed in the habitat landscapes.

Objectives and Methods

Objectives As this was the first new exhibit in Singapore Zoo to be planned as a simulated habitat, using landscape immersion, it would be useful to appraise it and test visitor responses to the novelty of a ‘full-immersion’ exhibit. ‘Primate Kingdom’ was also considered a candidate for studying visitor movements; both for their bearing on responses of visitors, but also as a study in microcosm of how visitors use a zoo. The particularly pertinent point about this is to find out, if possible, why attendance in ‘Primate Kingdom’ appears informally to be lower than expected.

Two hypotheses were suggested in regard to ‘Primate Kingdom’:

- That the naturalism of the surroundings coupled with increased activity (and absence of stereotyped behaviour) and numbers of the monkeys compensate for the greater distance between visitors and monkeys and their potential for being hidden from view; and

- That the whole development would bring visitors to this part of the zoo in greater numbers.

An additional objective was added during the course of the field work. That is to test visitor responses in a local ‘mother tongue’, namely Mandarin, spoken by the majority of the approximately 80 percent of Singaporeans who are Chinese (who learn it compulsorily in schools). The objective was to see if the English language surveys for this and other case studies contain any cultural bias.

Methods Two approaches were adopted to assess behaviour and attitudes of visitors viewing Primate Kingdom. First, a technique of passive observation was used in which visitors where selected at random at the various entry points and followed unobtrusively through the exhibit grouping. Their route and times and locations of pauses were noted as well as why they paused. From this it is possible to predict statistically the most likely routes visitors might take and, from the visitors' viewing times, the popularity of the individual displays.

In practice, the method involves a stop-watch and clip board and trailing behind the selected visitor or group of visitors, noting the entry and exit times, number of group members and points where stops take place, and timing these pauses with the stop-watch. A safe enough distance had to be kept to prevent the observer being observed and yet not too distant or a pause may be missed or the group might even be lost. Thirty-eight visitor groups were followed in this way.

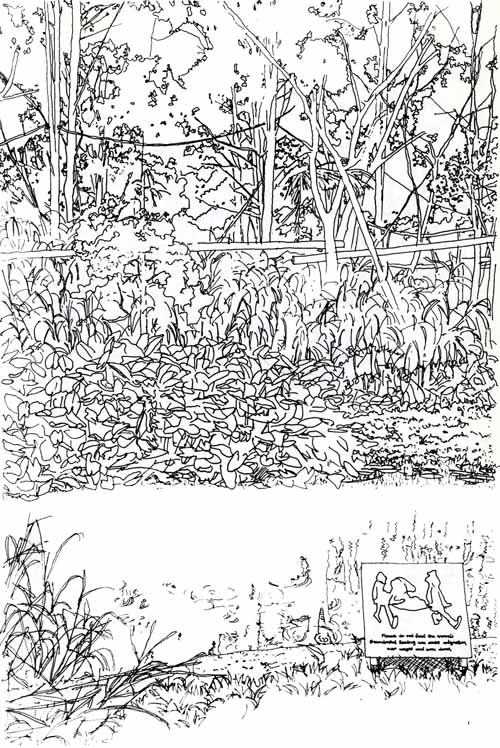

Figure 91 Silver langur (Presbytis cristata) moat at ‘Primate Kingdom’

Figure 92 Colubus (Colobus polykomos) and Patas (Erythrocebus patas) moat at ‘Primate Kingdom’

Figure 93 Psychological restraint: Free-ranging golden lion tamarins (Leontopithecus rosalia). Their night quarters can be seen

An assessment of which are the entry points was also made. Beside indicating the validity of the various routes through ‘Primate Kingdom’ as a predictor of visitor behaviour, it also revealed the proportions of visitors choosing to enter or pass by. Thus, traffic through the junction at each entry was counted for set time intervals and the choices they made were noted.

The second approach was to intrusively gauge visitors' responses to Primate Kingdom; freezing a moment of their experiences by asking them a series of questions. The survey instrument begins with several broad questions such as, ‘Do you like Primate Kingdom?’, which by themselves do not produce much information, but cross refer to other results. For example, the above question is followed by a request to rate Primate Kingdom on a numeric scale, which demonstrates, if nothing else, that visitors giving unqualified approval in the first question will qualify it in the second.

As with all the case studies, being first surveys, a broad range of topics were covered: accessibility, viewing, graphics and signage, planting. It was kept short and therefore there was little scope for follow up questions. For these reasons, the survey did not focus on any topics in depth; a broad picture was sought, which would identify areas for further study.

Two standard locations were selected in ‘Primate Kingdom’ for the survey work. Each next passer-by from the stream of traffic coming directly from further ‘within’ the exhibit was asked if he or she would like to participate. The two locations were at the two larger exhibits: the patas and colobus island and the silver langur island.

The voluntary nature of the survey means that there is a potential bias if the tendency to refusal or willingness to participate is greater in any demographic group. Another bias could result from visitor participating but not fully understanding the questions. Therefore, as mentioned, a follow up survey was translated into Chinese.

Results

Questions and answers The first questions relate to their coming to ‘Primate Kingdom’, such as awareness of it and ease of finding it. A language bias is evident with this question. The 54 percent who were aware of the title ‘Primate Kingdom’ conceals the fact that one third of Mandarin respondents knew this compared to two thirds for English language. However, the Mandarin respondents were more likely to say they had planned to visit these exhibits than the English respondents. About equal numbers, one fifth to a quarter, sought assistance from map signs or guides.

The next several questions proceed from establishing overall liking or otherwise of ‘Primate Kingdom’ to finding how visitors respond to the exhibits. No respondent to the English survey said they did not like ‘Primate Kingdom’, while 15 percent of the Mandarin respondents did. This is reflected in the numerical ratings: 7.98 in the English survey and 6.72 in the Mandarin group. Overall, the rating at the Silver langur was marginally higher than at the Patas exhibit, but the two groups had opposite preferences with the English group rating the Langur exhibit as high as 8.29.

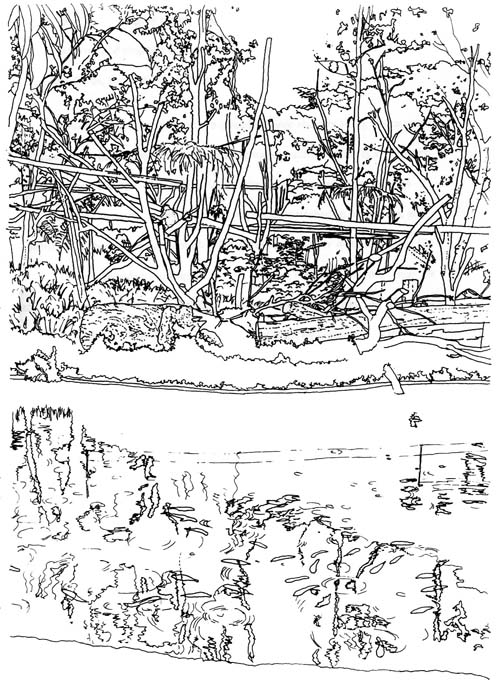

When prompted about the view and offered possible flaws with which they may agree, 65 percent of Mandarin respondents against 24 percent English thought the view flawed in some way. To gauge the strength of feeling, the island exhibits were compared with cages as an alternative. Only 9 percent overall--19 percent in Mandarin--preferred the cage option.

Respondents were asked to estimate the width of the moat at the two locations. This was to get a different perspective on the hypothesis that the widths of the moats, determined by jumping distances of the primates, detract from the views. Actual widths are seven metres at the patas island and five metres at the langur island. It was hypothesised that the moat treatment would cause them to be perceived as narrower than in reality. This does come out in the average of the estimates. The wider patas moat was estimated on average to be 4.91 metres wide, while the langur moat was estimated, barely on the correct side, as the narrower at 4.69 metres.

Figure 94 View of the Silver Langur Island |

Figure 95 View of the Colobus and Patas Island. Despite the jumble, horizontal and vertical elements are percieved as artificial |

The only significant finding on the planting scheme is that it was considered wilder (with both positive and negative connotations) at the langur site. Around 14 percent more, or two thirds, thought the planting was ‘about right’ at this location.

Graphics. The major graphics are placed in three shelters along the circulation route. Each as an educational theme, discussing topics such as ‘What is a Primate?’, diets, and communication. These were read by far fewer Mandarin speakers, 54 percent against 88 percent. Many Mandarin respondents wished to read them, and commented that there were not enough (58 percent) or that they were confusing (23 percent). Of the respondents in English, 68 percent said the graphics were ‘clear’ or satisfactory. Only a fifth were dissatisfied in some way compared to 85 percent of the Mandarin respondents. The obvious inference, confirmed by comments, is that Mandarin speakers would prefer graphics in Chinese. However, out of thirty-eight visitor groups followed, only ten - or 26 percent - actually stopped at one of the three graphic displays, one due to rain. Thus, nine groups spent an average of 122 seconds reading the graphics.

Demographic groups. Singaporeans were slightly more likely than average (70 percent) to say they would like to see the monkeys closer. A tenuous suggestion exists that only about half or slightly more non-Singaporeans and/or Caucasians would. Perhaps this is linked with the perception among Singaporeans that the patas moat is wider at 5.27 metres. Males, incidentally, grossly underestimated the patas moat width as 3.88 metres while they guessed the langur moat at 5.14 metres on average.

A difference of opinion on the planting between Singaporeans and non-Singaporeans was also found. The former were evenly divided in their responses while the latter were overwhelmingly in favour of the planting.

Semantic differentials While twenty one percent overall found the planting to be ‘too wild’, the adjective ‘WILD’ did not elicit a strong response either way when paired with ‘TAME’. The average response on this semantic scale was 4.99. ‘NATURAL’, on the other hand elicited a much stronger and more positive response of 2.65 when paired with ‘ARTIFICIAL’. The average of these two, 3.83, is considered more valid as evening out unforeseen connotations of the individual pairs of antonym adjectives. In proposing the adjective pairs for this test, it was posited that those who reacted negatively that ‘Primate Kingdom’ is ‘wild’, would therefore view it as ‘UNTIDY’. However this was not so; ‘wild’ and ‘untidy’ were thought of in opposite terms. It does indicate the chance nature of these pairings and the necessity of combining scores. If ‘natural’ and ‘untidy’ had been placed at opposite poles on the same scale, a different result might be expected.

Never-the-less, ‘untidy’ is so at variance with ‘natural’ that it is treated separately and just three paired results, W/N (= Wild / Natural), D/T (= Dangerous / Threatening), E/I (= Exciting / Interesting), are derived in Table VII.

Table VII PRIMATE KINGDOM: COMBINED SEMANTIC DIFFERENTIAL SCORES

SCALE |

ALL |

LANGUAGE |

LOCATION |

ORIGIN |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

English |

Mandarin |

Patas Monkey |

Langur |

Singaporean |

Non-Singaporean |

||

W/N* |

3.83 |

3.53 |

4.34 |

3.93 |

3.73 |

4.25 |

3.35 |

D/T* |

7.93 |

8.61 |

6.68 |

7.65 |

8.26 |

7.41 |

8.55 |

E/I* |

3.27 |

2.48 |

4.80 |

3.71 |

2.80 |

3.80 |

3.05 |

*W/N=Wild/Natural; D/T=Dangerous/Threatening; E/I=Exciting/Interesting | |||||||

The interesting features of this table are the greater level of danger or threat perceived by Mandarin interviewees and the inverse relationship between danger and excitement shown by the two locations. The langur island is perceived as more ‘exciting’ and less ‘dangerous’ than the patas and colobus.

Figure 96 Capuchin (Cebus apella) moat at ‘Primate Kingdom’

Figure 97 Lion-tailed macaque (Macaca silenus) moat

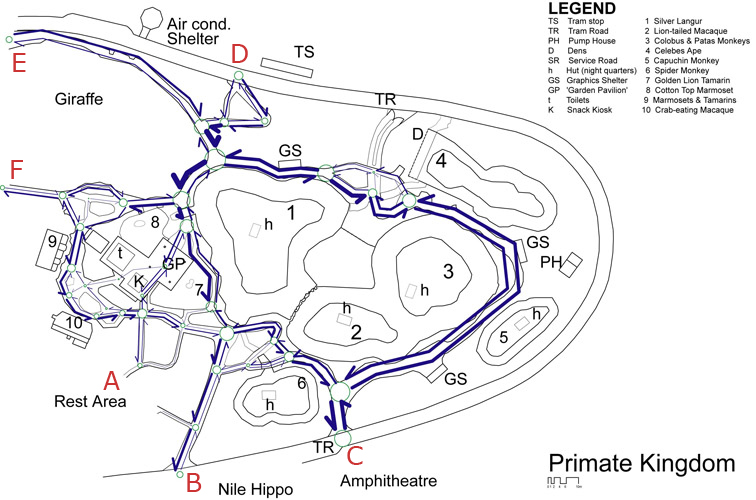

Passive surveillance study. There are six entry points into ‘Primate Kingdom’, which lies within a loop of the main vehicular and pedestrian circuit around the zoo. The greatest flows of foot traffic occurs at the entrance opposite the Amphitheatre where animals shows go on four times daily. The other important entry is from the giraffe enclosure. The remaining three routes are minor, but have significant circulation effects.

Table VIII gives percentage figures for the proportion of passing foot traffic entering at each point from all possible directions. In terms of the absolute traffic past an entry to ‘Primate Kingdom’, visitors walking along the northern loop, from the tiger exhibit, must pass three of the six entries unless they enter at one. The other three entries can be by-passed and the result for these are correspondingly low.

Figure 98 Plan of ‘Primate Kingdom’ showing magnitudes of visitor flows

Table VIII PRIMATE KINGDOM: PROPORTION OF VISITORS ENTERING AT EACH ENTRANCE

ENTRANCE |

ARRIVING FROM |

PROPORTION ENTERING |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(a) |

(b) |

(c) |

|||

Source |

per : |

- direction (%) |

- entry (%) |

Relative (%) |

|

A ('Rest Area') |

Zoo centre |

13.8 |

4.9 |

9.7 |

|

Nile Hippo (upper) |

- |

||||

B (Nile Hippo den) |

'Rest Area' |

12.5 |

6.6 |

7.6 |

|

Amphitheatre |

- |

||||

C (Amphitheatre)† |

Nile Hippo (upper) |

31.4 |

24.7 |

18.7 |

|

Nile Hippo (lower) |

26.3 |

||||

Amphitheatre |

94.5 |

||||

PBTL |

14.1 |

||||

D (PBTL)‡ |

Amphitheatre |

21.3 |

29.3* |

17.5 |

|

Giraffe |

40.8 |

||||

PBTL Tramstop |

33.3 |

||||

E (Giraffe) |

Pygmy Hippo |

62.5 |

63.5* |

41.9 |

|

Australian Fauna |

83.6 |

||||

PBTL |

- |

||||

F (Pygmy Hippo) |

Tiger |

26.1 |

6.5 |

4.6 |

|

Giraffe |

- |

||||

Total |

100% |

||||

*Note: |

|||||

D and E merge before entering ‘Primate Kingdom’ proper. The combined percentage is 55.4%. |

|||||

†Non-show times. |

|||||

‡ ‘PBTL’ stands for: ‘Pavilion-by-the Lake’--a private function area and tram stop. |

|||||

Columns b) is the proportion of visitors entering ‘Primate Kingdom’ at each entry, A to F, considering only those passing the particular entry; and c) is the proportion of visitors entering at each point relative to all other entries. See Figure 98 for a plan of the entry points, A to F. |

|||||

There are two patterns for those coming from the centre of the zoo, i.e. in the opposite direction. At non-show times (i.e. from about five minutes after each show to fifteen minutes before the next) visitors in move in much the same way as just described. Just before and during shows, visitors typically head exclusively to the Amphitheatre and perhaps half head back to the centre of the zoo and beyond afterwards.

Visual observation suggests at most a fifth enter ‘Primate Kingdom’ directly after a show, which is still quite a number.

Thus, except for the show effect, the two way traffic around ‘Primate Kingdom’ is about even: 54.1 percent come from the centre of the zoo and 45.9 percent from the other, clockwise direction. Each entry culls a certain amount from these flows, reducing the visitors passing the next, which leads to the question: out of one hundred visitors passing ‘Primate Kingdom’, how many will enter? This can be derived from Table VIII by progressively deducting from the one hundred the proportion entering at each point (column ‘c’).

Thus, all but eighteen visitors will enter ‘Primate Kingdom’ from the direction of the tiger exhibit, while as many as forty will pass by from the other direction without entering the exhibit. Furthermore, around seventy percent will enter ‘Primate Kingdom’. From the count made, visitors circulate in almost equal numbers in either direction; 52.2 percent from the centre of the zoo and 47.8 percent from the opposite direction. Trams and the Amphitheatre complicate this picture, but the assumption of these observed relative weights for the entrances is used to assess the results of the other phase of surveillance.

The other phase consisted of trailing thirty-eight visitor groups selected at random as they entered from one of the six entrances. Allowing for the visitor brought to ‘Primate Kingdom’ after the show, there is a reasonable match with the relative contribution of each entry. (Refer to column (a) in Table VIII).

Figure 99 Visitors choose among alternative routes in ‘Primate Kingdom’. They turn in the direction (left) towards which their attention is drawn

Within ‘Primate Kingdom’, there is also a circuit which goes around the three central islands, passing by the other three smaller islands on the outer side. To the right of the Amphitheatre entry point the circulation system becomes complicated with a number of small, capillary-like paths that bring visitors to the cage exhibits, a kiosk and toilet and to a view of the giraffes.

The principle features of the circulation pattern exhibited by the thirty-eight groups, comprising 422 individuals, are as follows:

- The major entry from the giraffe/P.B.T.L. is a net contributor of visitors; while the entry from the Amphitheatre experiences two way traffic about equally.

- The three minor entries are net distributors, i.e. they draw more visitors out of ‘Primate Kingdom’ than they bring in.

- Most visitors entering from the Amphitheatre move in an anti-clockwise direction. Most also initially go anti-clockwise from the Giraffe,, but fewer complete a circuit than those who initially went clockwise.

These features are illustrated in Figure 98 above in which the proportion of foot traffic in each direction along each section of path between junctions is shown by the thickness of the arrow. The total number of visitors passing either way through each junction is shown by circles with varying diameters.

The activities of the subject groups were noted as they were followed. The principle function recorded was the time and location of pauses to view exhibits or read signs and graphics. Of course, visitors may be viewing the exhibits as they walk, and it is not always obvious that they stop only to look at animals or read signs. It is assumed, however, that stopping before an exhibit is due to some attraction and a measure therefore of popularity.

Several important statistics are thus derived from this type of record. Firstly, around twenty-nine percent of visitors on average will view any given exhibit in ‘Primate Kingdom’ (the giraffe-view included). Secondly, the subject visitors spent an average of 12:06 minutes in ‘Primate Kingdom’ as a whole. Thirdly, an average of 6:07 minutes was spent statically viewing individual exhibits; the remaining time was spent walking. Fourthly, the average individual stop was 59.8 seconds. Lastly, each group stopped an average of 6.95 times (or about one per major exhibit).

An inverse relation exists between group size (average: 3.7) and the number of stops made. Thus, smaller groups were more likely to pause and larger groups more likely to keep moving. Possibly larger groups are distracted by their internal dynamics.

As stated earlier, the popularity, or attractiveness of individual exhibits, is assumed to be indicated by the frequency and duration of pauses by visitors; but this is a function of several variables besides the intrinsic qualities of the animals. It was hoped in planning ‘Primate Kingdom’ that the exhibit design would enhance the attractiveness of the animals. As exhibits rely on ‘passing trade’, so to speak, poorly located exhibits will receive less viewership, however. Competition for some can also be too great. The proximity of the Patas and Colobus island to the Amphitheatre, for example, draws people rapidly past these monkeys when announcements can be heard.

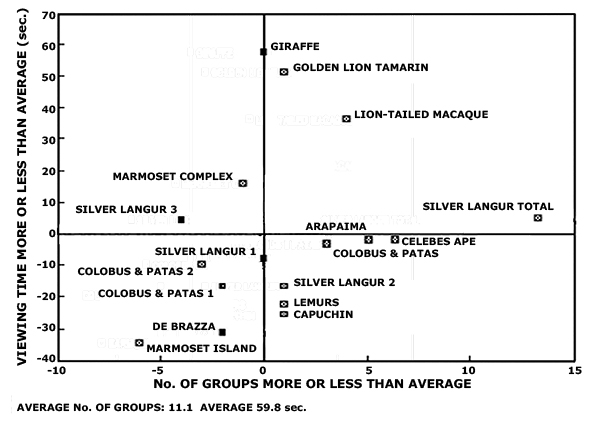

Fig. 100 'Primate Kingdom': visitor preferences by viewing time per group

The net result of these factors are summarised as pie charts above and below. It is interesting to note that of the three largest islands, the Colobus and Patas with arguably the most attractive looking and largest monkeys is viewed the least: 7.6 percent of groups stopped to view it.

Fig. 101 'Primate Kingdom': visitor preferences by viewing time weighted by group size. Only the silver langurs show and increase.

The result for the Golden Lion Tamarin is also surprising. This animal is very attractive and is located on a small island that the large, covered ‘Garden Pavilion’ over-looks. The kiosk and toilets here accounts for several long views by visitors waiting for their companions. The tamarins are conveniently located.

Fig. 102 Most viewed exhibits in terms of number of visitor groups and viewing times

Another way of looking at these results is to compare the numbers of visitor groups viewing each display against the average viewing time, graphed above, where the overall average is placed at the origin. For example, the lower left-hand quadrant contains exhibits viewed by fewer people for shorter times than average. The giraffe, golden lion tamarin, lion-tailed macaque and marmoset complex have the greatest holding power. The two largest islands receive the greatest exposure, being viewed for about a minute on average at each of three main viewpoints for each.

The best result (besides the giraffe) is obtained for the lion-tailed macaques, which almost forty percent of groups viewed, and for an average time of 96 seconds. The silver langurs are seen by many due to their position, but for little more than the average (59 seconds).

Discussion

A number of features of the combined studies of ‘Primate Kingdom’ are interesting and have wider significance. These various studies have: looked into cultural differences towards landscape immersion exhibits; assessed visitor responses generally to this type of exhibit; and studied how visitors make use of, and behave in, a relatively self-contained section of the zoo that could be a model for zoo-wide behaviour.

Differences were indeed found between language groups. Mandarin speakers did not react as favourably to the whole experience, though they were not negative in the absolute sense. Between the two selected sites for the conduct of the survey, they preferred the patas and colobus. Several factors can be stated in relation to this; whether any play a part and to what degree remains speculative. These are:

- The animals are larger and more colourful: the colobus are a striking black and white while the patas are golden brown to fawn. The silver langurs are grey except for their golden colour-phase young.

- The patas moat, while wider, is explicitly visible, reassuring visitors that there is little risk of the monkeys jumping across it. It more explicitly demarcates the visitor area from the animal area. The langur moat is narrowed by aquatic plants along its edge. Herbivorous fish (tilapia) keep vegetation in check in the patas moat.

- The langur island is greener. While both are well vegetated and have mature trees, the patas monkeys are more terrestrial than either the langurs or colobus and this tends to keep the ground cover short. Trees and shrubs also have a harder time coping with the more robust patas monkeys.

English language respondents possibly show the opposite preference for precisely the same reasons. The language differences do not necessarily mean the Mandarin speakers really feel insecure. Coupled with their less enthusiastic ratings in the E/I and W/N dimensions, it suggests that ‘Primate Kingdom’ stimulates senses and emotions, both positively or negatively. The more secure visitors feel, the more likely they will appreciate the heightened sensations. It is not absolutely clear whether this response pattern is due to the presence of wild animals and disguised barriers or the novel, wilderness-style landscaping generally, but the greater perception of wildness at the langur island suggests the latter.

Comparing the results of the two survey techniques--interactive questionnaire and passive surveillance--the two are found to agree on several points. Firstly, the questionnaire found a preference for the silver langur location over the location over-looking the colobus and patas monkeys. Surveillance of visitors' behaviour shows that the langur and lion-tailed macaque exhibits are the most popular. The obvious inference is that this is due to their locations immediately at the two main entrances to ‘Primate Kingdom’.

The two pie charts mentioned above show four main stopping points: at the two major entries and at two further points. The first two are at the silver langurs and the lion-tailed macaques, the second two are at the giraffe and golden lion tamarins. The patas island attracts about half the numbers of those four. Accounting for group size shows an even greater disparity.

The colobus and patas island suffers from distractions in the form of the highly active capuchin monkeys and Celebes black apes (macaques), which live opposite the two prime viewing areas for the patas colony. The path also forms a tangent to the island for most of the frontage. Visitors are not confronted with the display as they are with the langurs.

Another factor, not directly connected with landscape immersion, which may contribute to the lower regard of ‘Primate Kingdom’ overall by Mandarin speakers is their use of the graphics. An unwillingness or inability to read them possibly lowers their potential appreciation of the exhibits. The primary aim of such graphics is to interpret what they are seeing and help visitors to get more out of it.

Display modes may have two effects, indirect and direct. Firstly, landscapes that look like wild habitats, do not contain reassuring visual clues that they are only in a zoo. Visitors may have a sense of a lack of control over their environs. Secondly, animals placed in such a context will reinforce the wildness because they look free and visitors do not have the sense of regarding a caged animal. As stated elsewhere, citing Coe, the conventional zoo expresses human domination over animals and in this the zoo keepers act as the agents of visitors in their vicarious act of subduing wild animals. [1] In ‘Primate Kingdom, one has the feeling of encountering the animals on their own terms; they are not forced to behave in a way dictated by their human captors.

On the question of the drawing power of ‘Primate Kingdom’, it is difficult to say to what extent this development has boosted a less-frequented part of the zoo without conducting a zoo-wide traffic study. A clue, however, is provided by the decisions made at each entry point as summarised in Table VII above. Of the six entries, it was found that except in one case, visitors must consciously choose to enter from the main road. To do this, they must overcome the natural inertia that sends most visitors around the main circular avenue. The exception is ‘E’ at the lower frontage of the giraffe exhibit which draws 63.5 percent of passing visitors. Entry ‘A’ via the so-called ‘Rest Area’ also draws visitors unawares; however, this collects only 13.8 percent of visitors passing from the zoo centre, and this does not account for an alternate route to the amphitheatre.

The conclusion of this issue would need a follow up to the study conducted in 1986 by Churchman [2] of visitor movements and behaviour around the whole of Singapore Zoo. One finding of this study was that forty percent of visitors approached the (future) site of ‘Primate Kingdom’ from the central area of the zoo and sixty percent from the opposite direction. Because of differing methodologies it is not clear that the present study provides any indication of change since Churchman's study; however, he refers to the “profound” effect of the Amphitheatre which still occurs.

The strength of the entry via the giraffe suggests the pattern may be little changed. This draws 79 percent of passing traffic into ‘Primate Kingdom’. It forms an acute angle to the road (people tend to walk straight or veering paths), visitors are initially attracted by the giraffes, and it does not climb steeply as the Amphitheatre entry does.

In conclusion, the evidence reveals a major exhibit which has considerable drawing power due to the attraction of monkeys--along with lions and tigers, synonymous with traditional zoos--but which, with its non-traditional displays, takes some visitors aback. The tendency is for tourists and English educated locals to be more enthusiastic about ‘Primate Kingdom’. Regular zoo-goers will seek out ‘Primate Kingdom’; however, the non-regular local visitors is at the mercy of random factors influencing circulation patterns and may not find this area. To further the aims of the exhibit in suggesting to visitors the ‘right’ way of appreciating wild animals, i.e. in their own environment, and hence encouraging conservation awareness, ‘Primate Kingdom’ needs to be made more accessible. Particularly, the entry opposite the Amphitheatre is singled out, but also the three minor entries are noted as taking visitors away without seeing the bulk of the displays.

Once in ‘Primate Kingdom’, visitors read very little of the interpretive material, especially the Mandarin sample. Possibly the topics are too ‘dry’: the text and graphics address mainly biology and natural history. Little is mentioned to support the habitat theme. Never-the-less, the graphics were the biggest effort to date in support of a major new exhibit. The siting of the graphics away from the exhibits may play a part in their being less read. The question of bilingual texts raises the issue of budget limitation as well as whether only two language groups should be catered for.

On the whole, these are questions of refinement. Another area of refinement is to address the consistency of the habitat simulation and visitor's immersion in it. Both areas have a great deal of potential development yet. The positive responses suggests the zoo-going public is willing to accept the ‘new approach’ to zoo design and the balance can shift further--without neglecting the fundamental requirement of seeing the animals. Allowing for animals to retreat from view is one essential--but only one--feature of the new approach, and it need not conflict with viewing by visitors. Hidden animals may be due to random causes or it may be due to stress. If this new approach has validity beyond cosmetics, the stress factor will be eliminated.