The Role of Architectural Design in Promoting the Social Objectives of Zoos

A Study of Zoo Exhibit Design with Reference to Selected Exhibits in Singapore Zoological Gardens

by Michael Graetz

PART 4 CASE STUDIES

4.6 Cat Country Case Study

Background

From 1983 onwards, the big cat cages in Singapore Zoo were progressively reconstructed or modified to give the cat exhibits greater spatial volume and to introduce elements of landscape immersion and visual integration. At that time, the original cages built a decade earlier were seen as out-dated. Complaints from visitors were few, but it was anticipated that these would grow with time. At the same time, off-exhibit facilities were upgraded to improve ventilation and to refurnish den and exercise yards.

For the animals, the measures could only ameliorate the display conditions and be remedial to the holding facilities. Being one of the most heavily built-up areas of the zoo, the replacement cost of the entire building stock was considered prohibitive. For visitors, the intention was to portray the cats in more realistic settings, more attractively and to soften the impact of the cages. As with the dens, there were limitations as to what could be done. Far from accepting the cage as an inevitable distraction from any illusion of habitat, however, many features of the new displays overcome the faults of the old. These measures are discussed elsewhere (see page 64).

Despite these efforts a low level of complaints continued to be received. Behaviourally, few problems of stress were observed among the animals. The introduction of leopards into their new display saw them exhibit much greater activity than before. Being nocturnal and solitary by nature, a great deal of time in the day can be expected to be spent sleeping or inactive - unsatisfactory for many visitors - and thus, any activity might be seen as stress-induced. However, the classic signs of stress - repetitive or stereotyped movements - were not seen. In the old, square cages the cats could be seen each occupying a separate platform in each corner. When one animal moved, the others would shuffle around to new positions. They had little choice but to move if they were sub-dominant to the approaching cat and like-wise could not move or were forced to pace back and forth, if to do otherwise meant approaching the dominant group member. The remedy in the new exhibit was provided by a network of interconnecting timbers and tree branches. The possibility of avoiding contact with each other if they wish is allowed.

Generally in zoos, all the big cats are common (even if endangered in the wild) and though solitary in the wild (except of course the lion), much husbandry experience has shown that they can mix and socialise. As with orang utans, insufficient credit is often given to their intelligence, and hence adaptability. It is possible that social groups of otherwise solitary animals, where it can be achieved, can compensate for the boredom often experienced by zoo animals. The framework in the new display cage, which simulates the pertinent features of their forest habitat, allows certain degrees of freedom to the animals, depending on the stock numbers. Thus, having created an improved cage, much depends on husbandry and animal management practices. In this case experimentation determined the optimum number to display before the old, stressful situation recurs.

One further phase of redevelopment took place in 1993 when glass viewing was installed in the jaguar cage. The opportunity was also taken to re-landscape the interior and improve the cage furnishing for the jaguars, but the glass was entirely for the benefit of visitors, to improve their view of the animals and their perception of the cage.

Objectives and Methods

Objectives Against this background, a study was undertaken to test the level of dissatisfaction among visitors with the manner in which these cats are displayed. As mentioned, informally, it was known that some visitors object to these displays. Is this an expression of widely held views? On the other hand, dissatisfaction could result from a feeling of too few animals being on display.

The study also attempts to capture visitors' feelings about the style of exhibits in ‘Cat Country’; whether the efforts to reduce the negative impression of caged animals work to any degree.

The study also aims to capture data such as relating to overall regard, graphics for cross comparison with exhibit-subjects of other case studies, and to compare all results with other exhibit types. Lastly, since the aims are quite wide, it seeks indications of directions that follow up studies might take to more precisely pin down the effects of exhibit design decisions on visitor perceptions.

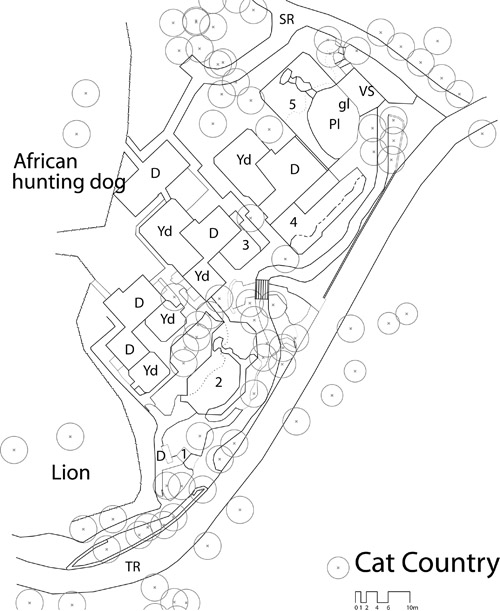

Methods Thus, a survey similar to that for ‘Primate Kingdom’ was designed with some questions in common with the latter and others particular to the cat displays (refer to Appendix B). ‘Cat Country’ in all, consists of five species of cats in cages (See the plan on page 227): leopard cat (Felis bengalensis); leopard and panther (Panthera pardus); caracal (Felis caracal); puma (Felis concolor); and jaguar (Panthera onca). The study specifically addresses the two big cat exhibits.

Figure 103 Plan of ‘Cat Country’ in Singapore Zoo

Figure 104 Jaguar (Panthera onca) glass viewing bay

Figure 105 Leopard (Panthera pardus) cage dominated by roof structure. See also Figure 29

Roughly equal numbers of interviews were conducted at the jaguar (23) and leopard (21) exhibits. These two exhibits differ in that visitors view the former through glass and the latter through mesh. This provides an opportunity to examine the differences between these display methods on viewer perceptions, since the similarity of these two large cats (which are often mistaken for each other by visitors) may neutralise their relative attractiveness.

Results

Questions Awareness that the cat exhibits collectively go under the thematic name of ‘Cat Country’ was greater at the leopard; 80 percent compared to 57 percent at the jaguar. The overall awareness level was two thirds. It is not conclusively determined which of two signs announcing ‘Cat Country’ is at fault. Demographically, awareness was less among those recorded as non-Singaporean, suggesting repeat visitation is a factor.

Being able to name correctly the cat being viewed was also greater at the leopard, 95 percent against 82 percent. Two factors seem to be involved, both compounding their effects. Firstly leopards appear to be more easily recognised by and familiar to visitors. Secondly, the educational graphics at the Jaguar Exhibit which discusses the differences between leopards and jaguars, appear to have the reverse effect of confusing some visitors as to which cat is on display.

Although the possibly leading question 3, Do you think it is a good exhibit? elicited a uniformly high response (84 percent), when questioned next whether they ‘like’ the cats, the positive response was almost ten percent higher. As with all the case studies, an attempt was made to get a numerical evaluation from visitors, and as with all studied exhibits, the ratings vary only within a narrow band of six to eight (out of a top score of ten). In the case of the leopard and jaguar, the ratings are 7.43 and 6.70 respectively. If this difference is significant, then it goes against the trend of other responses.

In perhaps the key question for the first objective, more than a third did not think the cats are ‘happy’ or contented. The detailed analysis is also interesting: while 30 percent felt the jaguars were not happy, this rose to 43 percent for the leopards. And while results for individual demographic groups have to be treated with caution due to their small sample sizes, the perceived well being of the cats was lowest among Singaporeans as a group of whom only half felt the cats were happy.

On the converse hypothesis, that visitors may be dissatisfied with the scarcity of animals, around three quarters say (question 6) there are enough but among the small number of dissenters, more were likely to say there were not enough than too many. This question was probably seen as a little loaded as it is asking them to judge, at the same time, a) whether the exhibit is over-crowded and b) whether they are unhappy with the number of animals they can see. This is borne out by question 9 on the size of the cage where visitors presumably looked at it more from the animals' point of view. The result also reflects a strong difference between the two cat cages with more than half saying the leopard cage is too small while only a third feeling the same about the jaguar cage. No one believes the cages are too big.

To get closer to the moral question of the acceptability of physical confinement as opposed to the question of whether biological needs are met, visitors were asked to compare the cages with a hypothetical moated exhibit for the cats and give their preference. Two thirds would like to see leopards behind a moat while only 17 percent expressed the same preference with jaguars. Caucasians, albeit a small recorded sample size of nine, interestingly particularly preferred the present mode of display for the jaguars.

Question 8 is aimed at gauging the response to viewing through glass or mesh by asking visitors if they encounter any difficulties in viewing. The result is not definitive, however: twenty percent at the jaguar as opposed to five percent (just one individual) at the leopard expressed difficulty; some at the jaguar turning out to be responding to the fact that the jaguars can retreat from view due to the limited extent of the glass.

The final two questions 11 and 12 cover the planting and educational graphics, the two principle means of telling visitors about the animals. For the purposes of this survey, habitat correctness was translated as the wildness or otherwise of the planting (although semantically, ‘planting’ implies cultivation). About twenty percent responded (both positively and negatively) that the vegetation is wild with a greater and more positive response to the jaguar. Paradoxically, the jaguar also elicited a slightly higher number (26 percent) saying the converse, that it is not wild enough.

All visitors claimed to have read at least some graphics with most giving bland approval. Critical responses amounted to 18 percent overall and 9.5 percent at the leopard - but 26 percent at the jaguar.

Semantic differentials Finally, visitors were asked to respond to the same set of semantic differential scales used at ‘Primate Kingdom’. On the ‘wild - tame’ scale, visitors rated ‘Cat Country’ as a fairly neutral 5.5 (zero is most strongly ‘wild’, ten the most strongly ‘tame’). Visitors were slightly more biased towards the description, ‘natural’ (4.28--again, most ‘natural’ is zero); however, both exhibits were considered to be very ‘well-kept’ (8.16—‘untidy’ is zero). While the exhibits are seen as reasonably ‘exciting’ and ‘interesting’, they are considered even more ‘safe’ and ‘secure’.

As a check against unforeseen connotations of particular adjectives, scale were chosen to be synonymous with at least one other in the group of seven scales. The ‘untidy - well-kept’ scale was intended as a synonym of wild - tame and natural - artificial; however, the results are so strongly reversed that the ‘untidy’ scale is left un-grouped and just three pairs of scales are considered. The three sets named for the zero-end adjectives are thus: Wild/Natural (W/N), Dangerous/Threatening (D/T), and Exciting/Interesting (E/I). Overall and broken down by exhibit, the responses to the combined semantic differential scales are summarised in Table IX

Table IX SEMANTIC DIFFERENTIAL SCORES FOR 'CAT COUNTRY'

SCALE* |

BOTH |

LEOPARD |

JAGUAR |

|---|---|---|---|

W/N |

4.90 |

4.83 |

4.96 |

D/T |

8.59 |

8.68 |

8.52 |

E/I |

3.15 |

3.48 |

2.87 |

*W/N=Wild/Natural, D/T=Dangerous/Threatening, E/I=Exciting/Interesting | |||

From this, it can be seen that the only significant difference between the leopard and jaguar is in the level of excitement or interest generated, which is greater for the jaguars.

One other interesting result is differences detected between the sexes. Females (recorded sample = 7) felt the cat exhibits were more natural and wild (3.75) than did males (5.19). They also regarded the cats as being more interesting and exciting (2.80) compared to the males (3.21), albeit by a slenderer margin. In most areas in all of the case studies, there are few significant differences between the sexes and the common bias toward males in the samples can mostly be ignored. This, however, is one case where equal representation of the sexes (less than a quarter were female) may have made a difference.

Discussion

Big cats are considered to be exciting and are a major draw of visitors to zoos. In terms of recognition and drawing power, lions and tigers come first, and then probably leopards or cheetahs. The survey shows that jaguars are less well remembered; most likely because, being spotted, their public image tends to merge with that of leopards. Despite this, the results of the survey indicate that the jaguar exhibit is more favoured than the leopard. The jaguars are seen as better off, their enclosure is sufficiently large and the exhibit is more natural and more exciting compared to the leopards. On general regard for the exhibits, no clear indication is found in the numeric scores. These are in the low end of the range for all case studies, but still positive. Because the result for the two cats oppose the trend of other results, doubt is cast on the validity of the measurement.

The obvious inference is that it has to do with the installation of glass in the jaguar cage. But there are a several ramifications of this inference and implications for design decisions other than that of installing glass to consider. For example, is the attempt to salvage the view through mesh a failure? And does this detract from the argument for landscape immersion overall?

As mentioned at the outset, the intention was to include elements of landscape immersion into the displays. The intention of this landscaping philosophy is to give an impression of natural habitat; break down the idea of barriers as separators of visitors from the animal's habitat; link a set of isolated exhibits grouped in a systematic collection (i.e., felids); and to give a correct educational message about the kinds of habitats the cats come from. Thus, planting and other features are as important as the explicit messages provided through legends and graphics.

The results of the re-development’s were quite pleasing: compared to the former straight forward and frank acceptance that a cage is a cage, everything now worked toward what architecturally might be called ‘a lie’. Every decision taken was an attempt to deny that the exhibits were cages. It is a definition of architecture as that which modulates space, and a cage defines a space explicitly. Landscape immersion introduces ambiguity and uncertainty, which is a thoroughly acceptable element to bring into architecture, but does it sit with a cage?

This author would argue that immersion techniques can apply to a cage situation and that the explicit objective of eliminating dissatisfaction is not achieved in this case because of, a) site constraints--the site is jammed between the original holding facilities and the visitor circulation route, and b) inconsistencies and contradictions in the application of landscape immersion techniques. It is arguable that if these factors had been overcome, the fact of viewing through mesh would still fatally flaw the exhibits, but between a simple, bare cage and the theoretical impossibility of a perfectly immersed cage it must be conceded that the present Leopard Exhibit is closer--and could have been closer--to the latter than the former.

To offer some criticisms, however, the following points can be made:

- The Leopard Exhibit, and formerly the jaguar also, allows the visitor to see at once the entire space available to the animals.

- The rear mesh can be seen as well as the front mesh. Those plants which do conceal the rear mesh in places are themselves protected from the animals with mesh.

- The exhibit depth is visually narrow in part because the ground plane is not flat and the steep rear is interpreted as unusable to the animals.

- There is no extended landscape or vista beyond the exhibit. Thus, impenetrable vegetation that screens the dens reinforces the explicit demarcation of the enclosure area.

- The roof supports of the cages are unfortunately ‘heavy’. Thus, even for those who appreciate the allowances for the arboreal nature of the cats, the vertical dimension appears limited.

On most of these points, the jaguar cage was already superior, and the introduction of glass indirectly overcomes the remainder. The ‘floor’ area of the jaguars’ cage is larger, 214 sq. metres against 144 sq. metres, which is important as they are less arboreal than leopards. The enclosure is dominated by a pool, which the jaguars swim in, over which fallen tree trunks are suspended to maximise their use of the space. Some of these ‘resting platforms’ are rather naturalistic. As mentioned, the water element extended beyond the mesh. This was sacrificed with the addition of glass.

The addition of glass-viewing does not simply do away with the faults of mesh. It can also control the view in such a way as to give the illusion of a much bigger space beyond. In this case, the frame does not permit the full extent of the enclosure to be seen. This of course means that the animals can also be hidden from view at times; a factor which comes out in the survey. The frame also cuts off the sight of the roof structure, so that the vertical dimension may just as well be unlimited; it does not enter the viewer's mind.

It was also mentioned at the beginning that the opportunity to re-landscape the cage interior was taken. ‘Gunite’ was used in place of some of the original natural rock and pebble beach and the planting at the immediate rear was raised so that a) the direct line of sight does not encounter rear mesh and b) the plants can survive the cats without mesh protection as, to reach them, the cats must perch precariously and, like most cats, will expend energy conservatively. Thus, the plants are able to grow more lushly and freely and not hug the perimeter, revealing its line more than concealing it.

The result is that viewers can forget that they are looking into a cage. The reminders have to be consciously searched for. It is clear too, that the result was achieved with the help of habitat simulation techniques and that elimination of mesh as a front viewing barrier is not the whole answer. And while without doubt glass is the preferred viewing barrier, there has to be recognition of other factors, such as monotony, if instead of a row of cages visitors troupe through a series of similar glass fronted shelters. There is a danger too, that animal exhibits become little more than animated museum dioramas, the contact and involvement with the animals lost--much like television. Aural and olfactory senses should not be overlooked either.

Glass cannot improve a poor exhibit, but it can help to overcome limitations beyond the reach of the designer, such as site constraints (a universal factor in zoos). For all its transparency, it still places visitors and animals in different worlds, unless it is handled in such a way as to immerse the whole viewing facility in the habitat. Perhaps the question is not whether cages can be immersed in the habitat, but can glass.