The Role of Architectural Design in Promoting the Social Objectives of Zoos

A Study of Zoo Exhibit Design with Reference to Selected Exhibits in Singapore Zoological Gardens

by Michael Graetz

PART 4 CASE STUDIES

4.7 Night Safari Case Study

Background

The Night Safari is a separate entity to Singapore Zoo and was opened to the public on 3 May 1994. It is the first zoo to be open only at night. Apart from this distinction, it differs from traditional zoos by also being based on the now established idea of zoogeographic themes. Its unique design features are, however, the lighting, discussed in another chapter, and the illusions that become possible through the control over what is lighted and what remains in darkness.

The visitor experience is a combination of a tram ride and several walking trails. As a rule, but not exclusively, the tram ride features large mammals (and one crocodilian) and the trails present small mammals in viewing situations more appropriate to static viewing on foot. The experience begins for visitors as dusk falls or after dark as they drive or ride along the one kilometre road approaching the Zoo and Night Safari. Guest relations staff are stationed in the Entrance Porch, which is illuminated with soft, warm light and has a large logo, a pair of cat’s eyes mounted on the gabled facade. This portal admits visitors to the entrance area, which contains all the visitor services--food, toilets, gifts, information--before passing through the turnstiles.

The entrance area does have three animal exhibits: two lemurs and ankole cattle. The latter is viewed from the restaurant terrace and the lemurs from two plazas adjacent the other facilities. The plazas and terrace are lit with ‘habitat’ lighting and separate the buildings from these animal ‘habitats’ so that the juxtaposition is not so artificial. The Night Safari proper only begins once these formalities are through.

Figure 106 ‘Night Safari’: binturong (Arctictis binturong) by day...

Figure 107 ...and by night

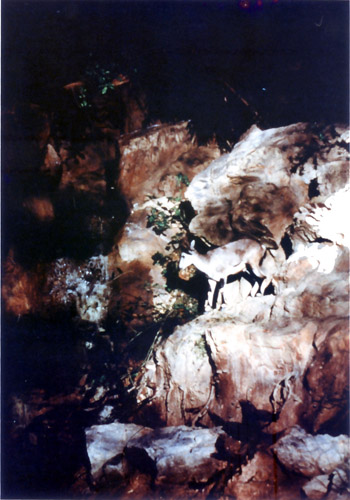

Figure 108 ‘Night Safari’: Bharal (Pseudois nayaur)

in the ‘Himalayan Foothills’ zone (picture: Stefan Byfield)

The Night Safari experience ranges from very large exhibits to very small ones. From a design standpoint, the smaller, trail exhibits are the more satisfying. Although advantage is taken of the darkness, many would work as daytime exhibits. However, the ability to show nocturnal behaviour is possibly what set apart the most successful exhibits. These include the fishing cat (Felis viverrinus), which actively fish, and flying fox, which are given the opportunity to fly. For the larger habitats, it is a question of balance between space for large animals or herds and compactness for viewing. Viewing distances do not need to be any less than in daylight, but as will be discussed later, quantity of light is not a problem, only the quality. Larger exhibits are more difficult to light attractively. However, these observation were arrived at after the public opening. The surveys here only shed light on the nature of the Night Safari with the benefit if hindsight.

Objectives and Methods

The Night Safari was still under development during the period of this study. However, when several groups were invited for partial tours to gauge the acceptance of the concept, the opportunity was taken to make an objective assessment of the response. Of the two groups surveyed, the Friends of the Zoo (FOZ) groups saw a more developed version of the incomplete experience.

The survey questions were structured around the unique features of the project and were designed to gather visitors’ responses to physical and environmental elements.

The categories of experience included the following: how the darkness or lighting affected viewing; thermal comfort; the realisation of the ‘habitats’ or animal environments including concealment of the barriers; particular highlights and general feelings about the whole experience (the latter through semantic differentials).

The survey method differed from the other case studies in that they were anonymous, meaning that no demographic data was collected. Thus, no correlations with age, sex or nationality can be made. Respondents received survey forms at the end of the tram journey. Around a half to two thirds returned a completed form. This sample is biased with respect to the general visiting public after the full opening. The FOZ group in particular will likely have a socio-economic make up different from Singaporeans generally and is obviously supportive of the Zoo.

Figure 109 ‘Night Safari’: Sign, shelter and bat aviary (Pteropus vampyrus)

(picture: Stefan Byfield)

Some questions were modified following the survey of the earlier group (called ‘media’). A more informative result was obtained when respondents were encouraged to express degrees of satisfaction or dissatisfaction with a given aspect, rather than answer ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

Results

Generally the results matched the assumptions made at the conceptual stage with comments emphasising the uniqueness of the experience.

Lighting. Much debate had gone into the lighting levels that most people would find acceptable for viewing. Few found the lighting either too bright or too dim but a quarter had some difficulty in viewing the exhibits. Other factors besides light played a part in this, not the least the speed of the trams (too fast). The light sources themselves involved some compromise in positioning so that quite often, the Zoo had to accept their visibility. Of those asked, yes or no, whether the light sources bothered them, only a small fraction said yes. Of those asked more neutrally if they had any comment about the lights gave more varied responses with 18 percent offering (often constructive) criticism.

Comfort. Offered a range of both positive and negative descriptions of the thermal conditions, most opted for positive ones with the majority agreeing it was ‘comfortably cool’ rather than ‘pleasantly warm’. Very often, they appended this with the comment that this was because it had been raining. The Zoo had also been concern about people’s fear of getting caught by rain even though, statistically, it rains less in the early evening. Although the respondents readily observed that late afternoon rain made conditions much more comfortable, no fears about rain were expressed.

Realisation. FOZ respondents rating the realism of the whole experience (however they define it) on a scale from one to ten gave it a rating of 7.8. The usefulness of this measure is hard to gauge since it depends on so many variables. A rough correlation with expectations exists, however, it being at the high end of the range of similar ratings gathered in other case studies. The Crocodile scored the lowest at 6.56 and the Silver Langur Island in ‘Primate Kingdom’ the highest (just) at 7.82.

Table X SEMANTIC DIFFERENTIAL SCORES FOR 'NIGHT SAFARI'

COMBINED SCALES |

FOZ‡ |

MEDIA‡ |

|---|---|---|

WILD / NATURAL / REALISTIC |

3.07 |

3.61 |

DANGEROUS / THREATENING |

8.14 |

7.1 |

EXCITING / INTERESTING |

2.18 |

2.33 |

ALL EMOTIVE SCALES |

5.05 |

4.71 |

ALL AESTHETIC SCALES |

4.33 |

4.82 |

‡FOZ=Friends of the Zoo;

Media = invited print and electronic media representatives. | ||

The Night Safari aims at landscape immersion by immersing visitors in nocturnal animals’ element--night; however, conventional elements of this approach were followed and moats are concealed or disguised as habitat features as much as possible. The result does not achieve perfection, even with fences, and a simple majority were aware of the animal containment methods much of the time. On the other hand, two thirds preferred the (then single) trail as an experience over the tram ride. Also, the second most cited highlight was the whole experience (15 percent). This was second after the Malayan tiger (Panthera tigris corbetti) which was the last animal seen. Other large mammals left strong impressions, including giraffes (Giraffa camelopardus capensis) and Indian rhino (Rhinoceros unicornis). After these, however, guests remembered several smaller animals. Altogether they nominated fourteen species, an indication of the memorability of these exhibits.

Figure 110 ‘Night Safari’: Barasingha (Cervus duvauceli) in the ‘Nepalese River Valley’ zone

(photo: Stefan Byfield)

Figure 111 ‘Night Safari’: Golden jackal (Canis aureus) in the ‘Nepalese River Valley’ zone

(photo: Stefan Byfield)

Semantic differential scales were used to gauge overall impressions of the experience and these are summarised in Table X. As with ‘Primate Kingdom’, excitement and interest are emotions experienced in safe and secure environments, therefore the apparent neutrality of the combined emotive scales. Again comparison with ‘Primate Kingdom’ suggests a correlation between naturalism and the excitement factor. It is interesting that when the Singapore Zoo opened in 1973, many were apprehensive about the safety of visiting the zoo. Since the opening of the Night Safari, visitors appear to take safety for granted.

Figure 112 ‘Night Safari’: Serval (Felis serval) and moat

(photo: Nihal Fernando)

Discussion

The ‘Night Safari’ was conceived out of the desire to develop a new specialist animal collection that would not compete with or be diluted by the existing Singapore Zoo. That this is achieved by having different opening hours is only part of the reason for the this development, albeit a compelling one. The variety of existing specialist zoos, including those based entirely on bioclimatic themes exploit logical divisions in the animal kingdom. The ‘Night Safari’ exploits the temporal separation of animals into night and day activity periods in a way not done before. [1]

The idea has occurred to others who have at least contemplated attempting something like it, but mostly such ideas have been to light parts of existing zoos at night. [2] In planning terms, the problems are similar to a zoo or theme park--crowd handling, transport, layout of service facilities, food and beverage needs. Night, with its different set of competing activities, such as television and cinema, and the compressed hours--seven p.m. to midnight--influenced planning decisions such as the intensity and orchestration of the experience versus the reality of the low key national park experience on which it is modelled. It is a compressed view that would require visits to many wildlife reserves to see, most of which do not permit night visits.

In pure design terms, many features had to be developed from first principles. The lighting has been discussed; and the moats mentioned. Dimensions for the latter were considered afresh not the least because of the intention to have animals not found in Singapore Zoo. Two prototype exhibits were developed initially to test lighting, control of views and the behaviour and positioning of animals. The results were encouraging. Even the habitat degradation that takes place under pressure from the animals is less obvious at night. The surveys here show that concealment of barriers was not consistent in the full scale development. Since those previews, wear and tear to the exhibit substrates has continued, but was quite minimal at the time; but, while it can be speculated that perception of this would emerge from a new survey, it remains less obvious than in day zoos. Trials with different ground covers--grasses unpalatable to deer--are ongoing.

The ‘Night Safari’ is a first in the world and was designed and built to completion with relatively limited trials; however, considerable scope remains to modify and improve within the structure created. For now, it can trade on its uniqueness and while it does not claim to be a real ‘safari’ it constitutes a further step in the movement to more humane treatment of animals in captivity by not conditioning animals to unnatural diurnal cycles. The numbers of visitors since opening demonstrate that the biggest fear--an unwillingness of humans to adapt to the photoperiod of nocturnal animals has proved unfounded.

Many implications for zoo design of this development have no doubt yet to be realised, even almost a year after its completion. The theatricality of the exhibits was, from the beginning, a truism. However, this is really where the significance lies: control over the visual spectacle approaching that of the theatre and not merely the visual: the balmy tropical night setting is a significant factor in the sensory appeal, at least to many tourists. It falls far short of real theatrical control, of course, but it is clear that the smaller road exhibits and the walking trails work best in the Night Safari. These give the greatest degree of control over lighting.

The three dimensional volumes, the forms and massing of object in these spaces, and the framing of views, all the basic factors discussed in Part Three in fact, appear to be even more critical at night. These definitely have to take account of lighting, and not merely the upper limits of viewing distances, or the throw of particular light sources. Planning is also affected, especially with tram viewing. Because the viewpoint is moving, perfect control is difficult, and was only achieved in a few places such as the jackal display. Longer frontages that continue around bends proved particularly problematic.

This preliminary assessment of exhibit design for night viewing is by no means definitive and views will continue to evolve. The Night Safari itself will also continue to develop in response. However, many of the assumptions on which it is based have been borne out in the result and it is difficult to say which is more significant: the original conception of the idea or the form it has taken on.